I’ve been doing some reading on GNS lately.

(Please don’t leave, I haven’t even gotten to the bad part yet.)

More specifically, I encountered this post by the irreplaceable Vincent Baker, which is a retrospective in some dimensions and a reinterpretation in others. And if you’ve never heard of GNS before, I think it can give you a biiiit of a primer about what it is. In short – it was a model of game design and play sensibilities, popular in online RPG theory throughout the aughts, mostly centered on people who favored one of the codified approaches to design and wanted to build for that. As a result, the other two (the G and the S) were a lot more ill-defined as outgroup taxa, and mostly served to rhetorically be “people doing the things we don’t like”.

As I’m sure you can imagine, this started a lot of fights. GNS is kind of synonymous with [that thing everyone yelled about forever] nowadays, and when it gets pulled back out it usually ends up being more yelling, followed by people going “sounds like we defined our terms differently” and storming off in a huff. Fun if you like miserable repetitive fights, but not worth much beyond that. We’ve got other models and new terms to yell about. (I like rambling about ghosts, for instance!)

But, if you dive through old RPG theory posts, it’s inescapable. And, really, the lens of it as being written primarily about Narrativism, the N of the three, and the other two being outgroup guesses that don’t necessarily model anything concrete, gives an interesting recontextualization to the posts that invoke it.

A history lesson, however, this is not. I’d have to do more thorough research for that, disadvantaged by the fact that I did not live through most of it, and I wouldn’t really have a point to make, beyond “hey, look at these ideas from the past, some are insightful and some are terrible.” Could that be fun? Certainly, I read these droplets of the past every so often for precisely that reason. But, it’s a bit weak as a thesis, for my tastes.

Here’s a post from about the era I’m discussing. 2008, GNS was in full swing in the zeitgeist. It’s discussing a concept, new in the terminology field, well entrenched by now – this post was one of the first clear sources on it, in fact. [Fictional positioning]. (I’ve also discussed this, indirectly, but I won’t link everything I’ve touched on here and there. I orbit a lot of topics, and if you read the last post I made, this is a direct expansion of a sidenote included in that one. It’s all recursive.)

Fictional positioning is… positioning within the fiction. Sounds rather self-explanatory, to some degree. It’s when you say, “I have the high ground,” even if there isn’t any mechanical meaning to that. It’s when you pull a gun from your holster, but the GM protests that you never established owning a gun, or a holster. It’s when you say “I walk across the room” and we assume your character has the ability to walk and exists in a room, on the side they don’t want to be. Fictional positioning is invoked when these things happen, and invoked when these things are canceled because the preconditions aren’t fulfilled. What do you mean, across the room, we’ve established there’s a hole in the ground! And you’re outside!

Obvious in retrospect, valuable to codify. Kind of goes to show how weirdly nascent this field is, that base concepts like that, which, I, for one, definitely took for granted, are dated that recent. (Almost 20 years ago is hardly recent recent, but on the scale of art? That’s very short.)

And, indeed, we see the three letters come up again. G, N, S. All framed in the context of how these three categories, which we now think of as one category and a couple of guesses, engage with it.

Here’s what Chinn (the author of this post) has to say:

And now, just one more mote of ado.

If you like miserable repetitive fights

Remember when I said that?

Unfortunately, I was talking about myself.

I enjoy arguments. I find them intellectually and socially satisfying. Many of the posts on this blog were born from arguments with people about RPGs and what we enjoy about them, and how those systems work. It’s a method to hone my ideas, in my experience.

It’s also socially unhealthy. Not as in for me personally, I’m quite alright, but it can poison a social context. If you’ve ever been anywhere on the internet that entrenches someone toxic and mean through argumentation, you’ll notice that the tone around the space gets worse, and generally it becomes a less pleasant context to exist in. You also tend to entrench a specific group of loud opinion-havers and people who agree with them, and further push away anyone else. This isn’t entirely the deciding factor of the course of RPG theory discourse in recent years, but it is definitely a contributing factor, and you can chart out many of the balkanized groups in terms of who is writing angry posts about whom. (I’m hardly an exception, if we’re being honest.) So it’s something I try to be cognizant of, and keep myself focused on interest in the perspectives of others, and improving the accuracy of models. Some amount of emotional bleed is always there, but an argument doesn’t have to be a fight, one would hope.

The primary cause of arguments, however, is still disagreement. And the primary cause of disagreement in RPG discussions is a difference of taste. People want different things out of RPGs, and if what I want is incompatible with what you want, and I come in with some rambling models of how to better build a system that does what I want, to you, who will necessarily lose what you want from that system in the process, because the two are mutually exclusive… well, you see how that goes.

Among the categories of people with distinct interests in RPG tastes and a similar propensity for argumentation, I’ve most commonly ended up clashing (again, not necessarily hostilely) with what I would describe as OSR people. The OSR is another digression, one with an unfortunately much more bitter history to read through – where the Narrativist movement had some dubious takes and general argumentativeness to its name, the OSR was for many years a seedbed of reactionary sentiment. Not merely as in terms of reactionary to RPG design; as in, “don’t worry, OSR stuff is no longer a gamble on if it’s racist” is a true statement I can make nowadays and only nowadays. Reading into OSR history may be enlightening as well, but, unlike the former sorts of history dives, which may be intellectually compelling, this one I definitely cannot recommend.

However. Nowadays, OSR stuff is no longer a gamble on if it’s racist. The OSR folks I discuss things with are, in fact, decidedly not racist, a quality I appreciate in the company I keep. And the OSR movement, “old school renaissance,” directly harkens back to the gameplay modes of old editions of D&D. Or, well, a nostalgic imagination of what those old gameplay modes were. Coherence in the present has come from discarding fidelity to the past in favor of clearer design. The goal of that design, and, by extension (though that reverses the causality) the play interests of the ones I’m deeming OSR people, are focused on gameplay fidelity to an imagined world, difficulty and danger that must be overcome through clever outmaneuvering within said imagined world, and a distaste for boundaries of both concept and gameplay. In a word that has moved to become somewhat synonymous with the movement – Simulationist. Our dear old S.

Now, I love boundaries of concept and gameplay. In fact, I long to be entirely bounded, and find the most satisfaction from games that properly construct a device for me to move within. I am a ghost that wants to be a mere droplet in a pipe, and never fly free again. So, you can see the core of where we clash. Discussing with the OSR people I know helped me consider my ghost model in more detail. It helped me see the various expectations put on GMs. It helped me see what it was I liked about Lancer, Panic at the Dojo, and etcetera – in contrast to what they found chafing about those games. A well-defined structure to play within, and strive to win at. A game I could play, and examine the game pieces as game pieces, and know if I was winning and how well. That is what I wanted, and what they found jarringly unrealistic. Their tastes did not align with what I would call the G in my own tastes. A Gamist I was.

This is all, of course, horrendously misapplied. I didn’t put much stock in labels from a multi-decade-old model that had been endlessly fought about, but these were the categories as they were split up, when GNS came up in discussion. (And then proceedingly, in fights.)

…Here’s a thing, though.

Remember this snippet?

This is exactly the thing I didn’t like. The thing I appreciated well-codified tacticsgames from not making me worry about. I get to a fight, the fight is balanced within its rules, I play within its rules, that’s that. It’s fun specifically for how it eschews fictional positioning as an element.

More interestingly – this is something OSR people would actively bring up to me. As what they liked, and wanted to do, and why they found games such as Panic constraining. They wanted to engage with the world, weaponize it, use it to be clever and bypass the obstacles in their way. Being deprived of that was a disappointment, and that was the appeal of OSR games, no?

And yet, it’s the G on that list, not the S, that categorizes this behavior.

Now, some amount of historical context is warranted. Most of the games I enjoy in this vein, Lancer in particular, but, really, many of them, owe their existence to D&D – specifically, the fourth edition. 4e in some ways pioneered this style of rigorously-mechanically-constrained combat design centralizing play, building on top of 3.5 already having codified combat to an unprecedented degree in comparison to prior editions. This led to it being rather maligned (in no small part thanks to an opportunistic marketing campaign by Paizo,) though, not a sales failure as I often see it reported. It would take a while for the indie scene to take to it as a pioneer, too – a post made in 2008, the same year as 4e was initially published, is to be expected for not accounting for its legacy. In fact, the GNS essays themselves were written around the turn of the millennium, and cite games like Shadowrun as Gamist affairs – because Shadowrun was one of the most mechanically-dense and optimizable options there was. Would things change if this all had been done more recently? Maybe!

But, remember. These are wastebin taxa. Gamism is written to cover [that behavior other people do that chafes with us (ie the people who prize Narrativist play)]. And that behavior is distinct from the specific game context it’s in. The behavior that was being gestured at, and not elaborated because it wasn’t in focus, was the direct commonality between me and the aforementioned OSR people.

The point of that example is that it’s using fictional positioning to try to win.

That’s what the G meant. For as much as it meant anything.

Playing to win

Most RPGs put a goal in front of you. (If you’re a non-GM player, at least.) Survive this dungeon. Steal this treasure. Rescue this dragon. Whatever it is. Sometimes, there’s a reward for it. Sometimes, there’s the opposite of a reward – you get there, and you stop playing. But the point is it’s a thing you want to do, and the experience of play is oriented towards you eventually doing it, or failing at that. Notionally, it’s probably something your characters want, so the motivations are in alignment if the players want it too. Plus, it gives an easy direction to go for all the cool challenges and interactions and whatnot. Going for the goal is playing the game.

It makes sense to try to win, then, right?

Just walking in a direction you’ve been given, metaphorically speaking, isn’t bad. I’ve had fun with that. But I mentioned challenges just now for a reason. Most of the actual tools a game might hand you as a player, or the GM as a GM, are focused on things that might stop you from achieving your goal. The goal that the gameplay is oriented towards, and your characters are motivated towards. If those challenges can’t actually stop you, then whatever you choose doesn’t really matter here, but if they can? Well, then, if you try, you get the experience of struggling to overcome a challenge, and if you don’t, you just don’t get to continue in the direction the adventure was built.

This is the logical foundation of what was prior being identified as Gamism. Naturally, since it’s human behavior, a logical foundation isn’t the only core of it. Using the manyfold model to try to summarize it, the emotional satisfaction of approaching a game like this comes mostly from fiero (the thrill of triumph) and ludus (the thrill of engaging with game mechanics directly). (In fact, the distinction I was noting between my tastes and the OSR tastes can be noted as the latter point – whether ludus fun is a priority, or if fiero is the sole focus.) And, I recognize that’s even more terminology to throw at you, so, in short, intuitive terms – winning is fun. Trying to win makes you win more, and both the trying itself and the increased number of times you win make for increased fun. If you enjoy that.

Winning is a thrill. It’s an easy kick to get, and to want to keep getting, as much as you can manage. So, the trick is, playing to win snowballs on itself. If left devoid of context, you just keep pushing more and more, figuring out new tricks and new combos to squeeze the most possible effectiveness out of a given build, the most effective way to bat your eyelashes at the GM and get them to okay your plot to cross this 10 foot chasm. You wouldn’t stop, unless there was a reason to.

But, unfortunately for this hypothetical context-absent you, they are about to die, because there is a reason. There’s an inherent maximum reward to this. Once you have a setup strong enough to always win, you don’t get any more benefit from continuing to empower yourself. You might get some of the tactile appeal of piecing cleverer builds together, if that’s your thing, but in time that fades away, too. You hit that threshold, and it becomes more trouble than it’s worth to go on. If that threshold comes too soon, you might not be satisfied by the game at all.

And that’s because the threshold of [you now win no matter what] is beyond the bounds of [interesting play]. Which means, feeding more context into the hypothetical, someone should have stopped you before then.

That puts a defined ceiling on how much room to push yourself there should be. If you can make a build that wins all the time, the GM needs to put challenges out that can match the power of that build. If you can argue a plan that the GM always has to accept, the GM has to put challenges in complicated enough that stringing several individually-perfect plans together becomes its own challenge. The worst-case scenario is they toss their hands up in frustration and punish you in particular, bypassing your efforts entirely. If they don’t do that, though… you’ve still got room to maneuver. There’s more blood to squeeze from this stone. As long as you aren’t always winning, and you haven’t conclusively hit the limit of what is possible in the system, keep trying new things, and you might tip the odds ever more slightly in your favor.

Now imagine if you’re playing next to that guy. The person following the logic of the above paragraphs. And, let’s take a more emotional appeal for a moment. Even if you don’t care as much about trying to win as they do. See how the GM had to spend so much time worrying about them, and figuring out specific counters? See how effectively they pushed you guys towards the goal, the thing that play is oriented towards? They’re in the spotlight. They have more control over what happens, and more attention from the other players. If that doesn’t make you green with envy – the next time an obstacle happens, and you’re responsible for resolving it, think about how less stressed you would be if you had the edge. This is something tuned for their nonsense capabilities, and you’re struggling to pass muster. If you fail, that might hold the whole group back, and they might get mad at you. There’s social repercussions to consider. Isn’t it better if you’re all on the same level?

This is what I’ve come to call [instrumental play]. It’s one of the first things I try, when I sit down with a game, and it’s what comes naturally to me. But, as I’m sure you can see – even in the context it’s adapted for, it has a lot of problems. It asks for an infinite treadmill out of an inherently finite system. There’s only so much better you can make yourself at a game, especially when a lot of that betterness comes from social adeptness, rather than anything mechanical. If your GM isn’t actually prepared to make challenges to match you, you will just win, and that might be fun for you for a short time, but the kick gets old, and nobody else will be enjoying it, either. If even one player isn’t on board with it, or even just on board with it to the same level, someone is gonna be unhappy. One of the most important skills for an instrumental player is learning how to rein it in. And that sucks! I hate reining myself in! I’m here to let loose and go all out and all that jazz.

This is, in essence, the behavior the G in GNS was trying to gesture at, as a “we don’t do that here.” Instrumental play has a lot of faults, if you value things other than getting to the end as efficiently as you can. Have you ever wanted to have your character get afraid and run away? Have you ever wanted to have them suffer a crisis of faith? If those happen, they might make you less capable of solving the problem you’re faced with. You’re hindering your effectiveness that way. The more instrumentalized you get, the harder that is to excuse.

That’s why it’s “instrumental.” A character is an instrument. A tool. A piece on the board, if you will. It’s a game, and winning takes effort, and the toys the game gives you are all about trying not to lose.

The catch

Here’s a question.

How do you know you’re winning?

One of the appealing qualities of instrumentalization is confidence. You know you’re doing your very best, and getting to where you’re supposed to go. You’re following the intended path of play, and that’s a good thing to do. So many complaints and horror stories about RPGs come from people refusing that, or simply not caring to, after all.

Sometimes, it’s pretty clear. You might not have a map of the whole dungeon, but whenever you find a new room, that’s progress towards seeing everything there is in this place. Eventually you do get to the end and find the princess. You just have to keep doing what you’re doing.

But not everything works like a dungeon.

What I’ve written about instrumentalization so far presupposes a clear goal to work towards. If there’s a fight, you know what you have to do to win it. If there’s a ball, you know who you need to slip the evidence to mid-dance. Etcetera. The more open-ended things are, the harder things get – because telling people ‘here’s what you need to do to win’ is not all that common. Open-endedness is often touted as a virtue of RPGs, after all.

For the most part, however, that open-endedness is an illusion. There is a goal, or, at least, an end state, the players are trying to reach. The game, and/or the GM, are expected to give little flags to signal that you’re going in the right direction, that there’s something to find this way. That’s much more common than there actually being a thing in every direction – much easier to implement, too, and if you’re the sort of person to enjoy a narrative with some focus when all is said and done, it works out better that way.

I recently had an opportunity to play the Magnus Archives RPG, running one of the modules it came with. Unfortunately, I can’t recommend it – Cypher disappoints me at the best of times, and it’s a very poor match for a mystery, of all things. But, it’s a phenomenon of adventure design that I want to talk about today, rather than that.

In short, the thrust of the adventure was an evil wasp nest that was doing evil magic that was planted by some suspicious people that we needed to investigate. Since it was an investigation, it was quite open-ended – go to places, poke around, do some skill rolls, hope you find some stuff. For the most part, freeform. We did find some stuff! Several clues, enough information to get us a sense of what was going on with the evil wasp nest, etcetera. Among those clues, we found a book. Upon reading the book, one of us immediately suffered some Stress (the game is operating somewhat in the Call Of Cthulhu milieu), and was told it involved some strange geometry and hurt to look at. Ominous! And definitely relevant to the case. We pocketed it for returning as evidence later, and didn’t read it again, on account of it was injuring us on a mechanical level, and intentionally reading more of the magic tome that does evil infectious bug things seemed like an obviously terrible idea.

As it happened, however, the adventure was designed such that a key piece of information was only accessible by reading the corruptive magic book and paying the Stress tax, three times. The detail we needed to find was about something growing within the hive, which was rather awkward, since we had already concluded the hive was growing, and, in fact, made a point of pretty soundly destroying it before we were done. The GM had to workshop that the specific element they were growing within it had managed to survive, and thus, we had only partially achieved the goal of the mission. Which we didn’t know was there, because we hadn’t read the book, because doing so was damaging us for no apparent gain.

Now, I do think there’s a fair bit to criticize about this as adventure design, which again loops into my dissatisfaction with the system. But, instead, I want to pivot to a conversation I happened to have a few days later, in another context, about Call Of Cthulhu proper.

The key argument of said conversation was – Sanity loss (and, by extension, Stress damage in this context) is a flag. It damages the player, yes, but it signals to them also – here is where something interesting is, you should pay the tax and see it.

This was both interesting and confusing to me, mostly because it had just never crossed my mind. I’m not much of a Call Of Cthulhu person, I haven’t played a lot of it, but, just as a general principle when I’m playing games, I try to avoid random losses of resources. If something demonstrates itself to be a fire, I pull my hand out and don’t put it back in unless I know it’s worth doing. It’s a resource-conservative mindset, which isn’t always instrumentally correct, but it is, usually, pretty consistent. What I hadn’t been considering was the resource cost absent the context of the game. That is, as a piece of communication from the GM to me (or the adventure module to me, or etcetera). And, if I had, I would have probably considered it as a warning. Touch the fire, get burned. Here’s something dangerous, keep going and you’re gonna keep getting hurt. This would be a stupid and inefficient thing to do. Right?

But, that’s not always the case. As evidenced by people who were COC GMs in that conversation nodding along and saying that, yes, they absolutely use Sanity taxes as a signal that players should go here. The theory was, as they explained it – players are expected to look at Sanity loss as an inevitability. Not something they should minimize, but, rather, an inherent phenomenon of walking down the track of the game. Engage with eldritch horrors, lose Sanity, insert rest of game there. As a result, not losing Sanity is a downside flag. It means that you’ve missed the path you were supposed to go on. That’s the sign of the goal, not a wall.

Except also you can avoid some Sanity loss while moving towards the goal if you’re smart about avoiding the hazardous parts, and that is the most ideal play, so you should be doing that, from an instrumental perspective.

And there’s the muddle.

See… I’m bad at picking up implications that are left unstated. That’s part of what draws me to instrumental play. It’s clear in both its motives and the context it necessitates around it. Have goal, move towards goal. It’s simple. Similarly, if a game hits me with a mechanic that I know will be bad for me if it keeps happening (Sanity loss, Stress buildup, etcetera) then I’ll know that’s a dangerous thing, something to avoid having happen again if I can help it. An invisible manner in which that is also a lure to compel me to engage more, if it’s not stated by the game’s design as a reward and it’s not stated by the GM as a norm of play… well, what happened in the Magnus Archives game is what happens. I don’t even realize that I was doing something wrong until I get to the end and am told I was expected to come to an entirely different conclusion.

Instrumental play is preconditioned on having a sense of what you’re supposed to be doing. One of the big failure points of GMed RPGs as a medium is lacking that sense. I think every game that has gone wrong for me, I can point at least in part to an absence of direction as part of the problem.

And the thing is, if the GM is the one providing that sense, it gets worse. GMs have a lot of conflicting responsibilities to their name, but among them, if you’re good at instrumentalizing yourself, they’re going to feel obliged to stop you. Can’t let you win too easily, or the whole experience breaks down. (Maybe.) This is where the thing I said before comes in – the GM has to add more and more difficult challenges in front of you, and you run the risk of them getting frustrated and actively singling you out for punishment. Would the latter be wrong of them? Yes, of course, but it would also serve to rebalance things if you’re far ahead of where the other players are at in terms of ability to engage with the game. No options are good, in a sense.

If you get on a treadmill of harder obstacles and more power, you have, in a sense, bought into an illusion. Your optimizations don’t actually make you any more efficient, since you’d be facing a weaker challenge if you hadn’t bothered. It’s an illusion the GM is spending active effort into having to maintain, too, which isn’t great. (If you’re seeing a comparison between this and certain progression systems, that’s another story, but – yeah, many of those are illusory treadmills for the same reason. Giving the player a sense of satisfaction at getting more efficient, more powerful, more instrumental; without actually having to reckon with the consequences of that.) Is that satisfying? It can be! I find this sort of treadmill to be a good way to ease off my instrumental brain, for games where it isn’t helping much. But it doesn’t do the same thing. It’s still, ultimately, smoke and mirrors.

Instrumental play, more than many approaches, highlights the PvP nature of RPGs. It sets you against what the GM has in store for you. A lot of the time, it’s a game imbalanced enough that the GM could just wave their hand and win instantly. So it can really only ever go one way, for the most part. And that means, to truly instrumentalize yourself, you have to learn to read your GM in and out. Know when this is an obstacle to overcome, when it’s a warning that you put your hand in the fire for no reason, and when it’s a flag that you’re on the right track, which just happened to come with a bit of damage for your trouble. If you don’t know, or you guess wrong, it’s easy to fail entirely, no matter how well you play.

…

Stress

A lot of my RPG theory is born, I think, from finding it rather stressful to interact with people.

Now, there’s a lot to unpack there, and a random blog post for the public eye is not the place to do that. But, I do think it’s relevant context, and a lens worth considering. People are stressful! Socialization is a complex tangle of rules and norms, most left unspoken and yet harshly punished if you transgress. It’s not a very well-designed system, in terms of user experience – and it’s a fundamental substrate all non-solo RPGs are built on. Understanding how that influences the shapes and structures of play is fundamental to understanding the medium.

Instrumentalization is, in part, a social gambit. If you get everyone on board, then you don’t have to worry about that anywhere near as much. Are people passively unhappy with you? Are they charmed by you, and going to go out of their way to assist you? If you’re all working for the same goal, and you’re all focused on efficiently achieving that goal, these things don’t not matter, but they do matter a whole lot less. The implications of being favored fall away, for the most part, in the face of the implications of the rules and structures of the game.

If the gambit gets declined, of course, if the group isn’t on board with instrumentalization, you are now eclipsing them ‘unfairly’ (‘unfair’ in that you are not doing so by engaging with what the group wants to be the deciding factor of player significance) and that likely itself becomes a social repercussion. Which makes for a complex negotiation phase when moving into new playgroups – though, that phenomenon is certainly not unique to instrumentalized play. That negotiation always happens, and if left unsaid, it happens in the underlying passive-aggressive social layer of approval and disapproval.

Interestingly enough, though… social anxiety or no, the stress of instrumental play doesn’t end if the gambit is accepted.

Winning is hard. (I mean, sometimes it isn’t, and the GM is primed to let you win – but in that case, instrumentalization really flounders against itself. It expects winning to be hard.) You have to be on the ball, and doing you’re best, and you’re going to make mistakes. We’re human, it’s what we do. Sometimes, even if it isn’t necessarily a mistake, you’re going to make a guess and get it wrong. Mispredict something. It’s especially difficult when what you’re playing involves predicting what the GM wants you to do, or will let you get away with. There’s many variables to juggle, and if you don’t juggle them right, you’ll fail.

The first thing I feel when I win an encounter in an RPG is relief. I’ve made it through. I can relax now. I’d wound myself up a lot there, but it’s done now.

It’s satisfying, too, don’t get me wrong. I’ll be pleased by my success, happy to bask in the reward. But the first thing that hits is relief and fatigue.

It’s tiring, being locked in. It’s stressful. And it gets more distressing when all that comes to naught – either my best wasn’t good enough, or I couldn’t bring my best, and both are bitter pills to swallow after however much time it took stressing about trying to win. Loss is a looming threat, on an emotional level, entirely because this is a thing I care about. That’s tough! Even if everyone’s on board!

I don’t think my heart could take a game that’s all instrumental, all the time. I’ve played them, and at best they’re a sometimes food for me. I’ll need time to recover, and needing time to recover after a campaign of an RPG isn’t necessarily to be expected.

What I’ve found works best, then, is segmented play. A game with modes where I’m supposed to be going all-in, and ones that serve as breaks. A release valve of putting around between fights, to keep the emotions down.

I think these kinds of breaks are valuable! Even in a broader conversation than about instrumental play at all, just, having break time in between tense modes of play is valuable for any multi-session-length RPG, for the health of the players. It’s a good design facet to keep in mind, and it’s why things like downtime mechanics that serve almost no purpose beyond as scene framing are actually quite handy to have.

However, we’ve hit another intuitive snag. One that circles back around to our example of fictional positioning, of all things.

We just had a tough fight. We’re putting around. Getting a few character moments in, maybe. There’s another encounter on the horizon, but we’re not there yet, we still need to de-stress a little. Something about a beholder.

Someone asks if they can find a barrel of tar nearby.

We are now instruments again.

It’s a sensible consideration, right? Yeah, we’re stopping to rest, but there’s another fight coming. We have time to prepare. The smart thing is to use it. It’s much more difficult to use the environment in combat-time, setting it up to our advantage is clever, etcetera. Hardly any complaints from an intuitive level, and from an instrumental level, exactly what we want.

But now, I can’t relax here. This isn’t a break, it’s another phase of the test. If I don’t figure out the most efficient use of my break time, the best way to prep us for what’s coming next, I’ve messed up. I can’t afford to be doing these side character moments that I wanted to get to even though they don’t mean anything gameplay-wise, I have stuff to do! Heck, what if there’s some sort of character bond system to focus on? If I don’t make my character interaction scenes as efficient and value-positive as I can, I’m sabotaging myself!

This forms one of the big boundaries around the sort of break I need, and definitely one I encounter the most opposition to in discussions of game design: breaks need to be unimportant. Structurally, that is. They can be meaningful to the players and the stories they’re writing, in fact, I find they’re quite valuable in games that otherwise limit the player capacity to focus on character moments and interactions, but they can’t be vectors to win. At most, I find the aforementioned downtime systems to work decently well as a compromise – in Blades In The Dark or Lancer, you pick from a list of downtime options based on the benefit they give you, and then what happens when you play them out won’t change the game. It doesn’t shift the mechanics, after that initial choice – it’s a little bubble of break time, where you can do the wrong thing, have a character self-sabotage a bit, and not have it come back to bite you. It’s nice.

It’s, I imagine, what everyone who doesn’t play like this gets to experience, when they aren’t stuck next to a player like me.

…Kind of.

I started this post by discussing GNS, and its relationship to instrumental play as a vaguely-defined “other people do this, we don’t want to, let’s make our own thing for us instead of them”. I’ve had, in various discussions, the concept brought up that this play approach is inherently perverse, and, perhaps, there’s something wrong with me for engaging with it at all. It’s the mark of an inherently toxic or to-be-avoided player, the theory apparently goes.

Now, I’m not one for pathologizing preferences, especially my own. I happen to think that I am a perfect being and everyone could stand to be more like me. But, there is one factor to all this that I’m interested in noting, and picking apart a bit.

To wit – it is a worse experience to play alongside someone instrumentalized, if you don’t enjoy that sort of thing.

Forget the social gambit consideration, and just look at the experience of play. You’re faced with a challenge. The primary way you can engage is by overcoming that challenge. The guy next to you is really good at overcoming the challenge. You would like to have the spotlight every so often.

What do you do?

You figure out a way to outcompete. You get better at overcoming challenges yourself.

Or you don’t, and the GM starts posing tougher challenges to match the next guy, and now you aren’t even getting your normal share of success. If the next guy (I shoulda just named him) were to vanish, you probably couldn’t even progress at all.

If you’re not happy with that, if you don’t care too much about that, if overcoming obstacles is just what the game happens to mechanize and not what you care about? Yeah, I’d imagine you’d be peeved at Steve over there (I named him). You wouldn’t really be wrong to, either. Your experience lost its appeal to you, and your capacity to engage with it, all because of the way he approached it. One of you needs to change, and, in the passive-aggressive social context where just talking expectations out would be a faux pas, Steve has you beat, because the game is working for his side more than yours. Pushing him out of the group would really be the best option you have, and making sure someone like him doesn’t get to join back in.

(…If it wasn’t clear, I think [the passive-aggressive social context where just talking expectations out would be a faux pas] is a terrible place to be and this method of resolving this situation would make me think poorly of everyone involved. However, getting people to talk about their expectations is hard, doubly so when people don’t understand their expectations, so I get why it happens.)

Probably one of the best ways to avoid this mess is to communicate from the designer end. To tell the players, hey, please play like this, and not like that. I don’t want you to be instruments. Or I do! In a sense, that’s what the [Narrativism as game jam] perspective Baker wrote about was taking – a series of games all made based on a communicated designer intent to have players play for what drama they could find, and not try to win over everything, or any other such goals the players might have (the S was its own thing, potentially, for instance). These are gradients, of course – I brought up Blades In The Dark earlier as an example of a game with a somewhat comfortable rhythm for instrumental play, despite it being a descendant of the Narrativist game jam, because it actually can work that way. But the request is still there.

I read Eureka recently. It’s an urban fantasy mystery game. (The full title-and-subtitle are literally Eureka – Investigative Urban Fantasy.) For a lot of the time spent reading it, I was rather unsure of what to make of it. The most important segment for me was actually nestled away in a piece of GM advice – the GM is asked rather emphatically to avoid making their own adventures, as that would be a lot of work, and instead rely on the preexisting wealth of modules for games like Call Of Cthulhu. Or, in other words, the design of Eureka can be looked at from the lens of being a game built to run Call Of Cthulhu modules, which made several things make a lot more sense to me. I definitely don’t think it’s the sort of thing I would want out of a mystery RPG, but for those intrigued by the prior few sentences, I do suggest giving it a read.

That’s not why I’m bringing it up, though.

(Do note, this is a copy of a game in development, so a few placeholders-for-images occur here and there. The text is the important part, anyway.)

These sections are placed one after another, in explaining the principles of design and expectations of play for the game. Which I do really appreciate! I’m glad that games doing this sort of thing has started to catch on. It is nice to be informed as a player and a reader what the game expects of me. And, for the most part, these sections seem clear to me. I should follow the incentives of the game and the interests of my character to preserve their survival and ability to follow through to the end of the investigation. The difficulty should be tuned high from the GM’s end, because a certain or highly likely victory is unsatisfying in comparison to a hard-fought one. From an instrumental perspective, I ought to be on board with this. Except, the first thing they ask is to discard my prior notion of winning. In fact, they go as far as to propose that I “play-to-lose”. Which seems to declare an upper bound on how hard I should be trying to solve the case, surely. Specifically, if a decision would make significant progress, but remove an interesting situation, it seems I should avoid it. But, then, what if I consider remaining while at low Composure to be a more interesting situation, and I stay in a dangerous context? My understanding is the answer would be that’s supposed to happen, but that also means the incentives the systems are producing are now pushing against the goals it sets out for me. How do I know when I’m doing too much instrumentalization, and it’s sabotaging the interest? How do I know when I should be doing more? The answer is left unclear, and it’s on me to figure out.

And, to be clear, I understand why. But this, more than anything, is what stresses me out about instrumentalization. The idea that there is a too-much. There is a ceiling, and if you go past it, you should not have. But we don’t get to tell you where the ceiling is. You have to figure it out, and if you guess wrong, you’re Steve.

In the ever-spinning gyre of RPG discourse, there’s a term from some 10 or so years ago. “Flashlight dropper.” I believe it comes from Call Of Cthulhu gameplay, even, though I’m not certain of that. A flashlight dropper is a player who, when presented with a scenario frightening to their character, says something like, “I drop my flashlight and run away”. It’s a derogatory term. The point is, this action is so obviously foolish from an instrumental perspective, not only abandoning the group but depriving yourself of a valuable tool for no reason (at least keep the flashlight when you run away!), that players who do it are disruptive to any even-slightly-instrumentalized arrangement. If you have an objective you’re trying to fulfill, that act is actively sabotaging you.

If I were playing Eureka, I would leave this intro post simultaneously thinking that the game expects me to drop flashlights, and that group defeat would be inevitable if I did. Part of the logic behind flashlight dropping is that real people would do that. Real people are stupid! If I was panicked, I might drop my flashlight before running away from a monster. Would that make for a more interesting story? I don’t know, I’d be more concerned with the monster than finding out. But if the mystery was set up as Eureka asks it to be, I’d interpret that as a significant detriment for no gain, and telling the other players that our goal is to have a fun story, so actually this was fine, would feel pretty flimsy. It’s hard to look someone in the eye and say that counts as a win.

What even is a win?

I tend to get pretty aesthetically invested in my characters.

(This is another reason why OSRs don’t quite work for me. They’re pretty strong on characters as disposable tools, as far as instrumentalization goes.)

As a result, this defines, for me, a secondary dimension of winning and losing. If I get through a situation with my character looking competent and showing off their strengths, I’m happy! If they look silly, and don’t get to play to their strengths, I log that as a failure. It’s not a win in terms of the goal the players are working towards, but it’s a win for me in specific, and it’s something I’ll stop to consider before sacrificing.

That’s one of the ways to make instrumental play compelling on other dimensions, in my experience. Force players to choose between priorities, sacrificing one goal for another, and you can get interesting results. As a player, I enjoy dilemmas like that, and they’re much less solvable. It’s not a matter of picking the right answer, it’s deciding what answer is right. They make nice breaks from the puzzle of optimization.

I’ve been chatting with someone recently who has rather similar interests of play, especially in terms of instrumentalization. But, on this point, we diverge. She’s discussed modeling her characters’ dignity, well-being, and situation in life as resources to be expended gleefully for the sake of further resolving the primary goals of play. And this produces problems! Dilemmas like I proposed in the last paragraph are no-brainers to her, and when games bake them in, the balance gets thrown entirely out of whack. It’s just not a win condition for her, so it’s free points.

A lot of dilemmas like this rely on aesthetic player interest, one way or another. Endangering an NPC only means anything if the players care about that NPC. Losing a mission only means anything if the players care about winning missions. Most commonly, the ways games have to designate things as goals and stakes are one of: [here is a thing, please bond with it] and [here is a source of more power]. The former is where things like caring if your character looks good comes in. The latter is what XP is. Why do you care about winning the mission? You want to level up, don’t you? And you want to level up because that makes it easier to win missions. It’s a cycle, or so the theory goes.

There’s also a third option, [the game doesn’t continue unless you do it]. For games with high lethality, or even games like D&D 5e that just have moderate lethality but are happy to lock you into it, that’s why winning a fight is a goal rather than just surrendering from the get-go every time. (That, and surrendering not being a codified option, but you can always intentionally beat up your own party until you go down. And that sounds ridiculous, yes – but, remember. If that gets you to move on, and it gets to the end, that’s only a defeat if you happen to care about the things lost in the process!) In practical terms, this is what things like dungeons are. If the GM plops down an adventure in front of you, and you decide not to bother, then usually this is why that’s not an option. However, usually, people don’t want to invoke this one, so it’s a bit invisible vs the other two.

[Here is a thing, please bond with it] is very unpredictable. Whether the players care or not about a given character, or if they look good, or if the kingdom is recolored purple instead of red, the system really doesn’t know. Usually, this is left to the GM to figure out. They know what the players care about, they can put that at the end of a quest, or put it at risk if they don’t face this challenge right now. This is also hard to systematize – at best, you can say “put something the players care about here” as an open slot in a defined obstacle, and the players will figure something out to go there when the time comes. You might be able to say “players are obligated to care about this person and want their wellbeing,” but I’m not sure how consistently declaring that as a system would land. It’s usually all too interpersonal and fiddly for that.

The second option, though. [Here’s a source of more power]. That has potential.

…Or, at least, it seems to.

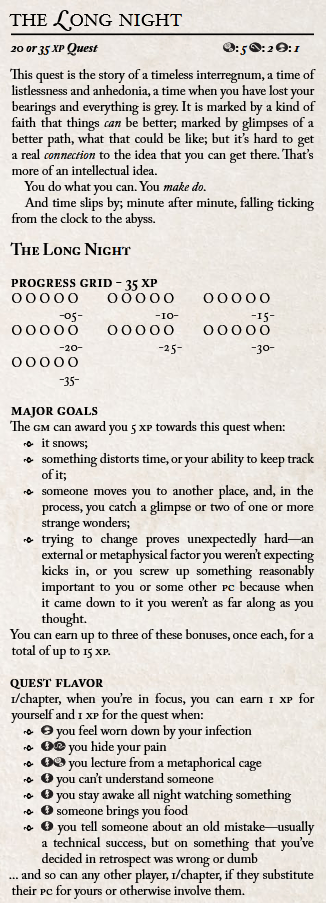

Here’s a bit of tech from Glitch.

This is a Quest, and it’s design that I absolutely love, except for the instrumental part.

Quests are composed of two lists that feed into a progress bar of XP. Major Goals, which are big events that give you a solid chunk of XP when they happen, and Quest Flavor, which give you 2 pips (XP for yourself is allocated to any Quest of your choice), and can happen much more consistently. More specifically – you, the player, have the power to just declare that a Quest Flavor happens. They’re little pieces of authorial power that you always have access to while it’s in progress. If I were playing this Quest, I could just say, hey, someone brings me food. And they do! However that resolves. They aren’t materially significant, you don’t use Quest Flavor to overcome obstacles in your way, but they do let you shape the world around you to fit a certain tone, and, since players are allowed to write their own Quests (with GM approval), you can get pretty nuanced with the vibe they create. As narrative-shaping tools, they’re quite nice.

Writing Major Goals gives players a way to signal interest in dramatic moments they might want to have happen, then. And, more broadly, the XP track helps to make sure that you’re never stuck in the same narrative arc for too long, while still being sure it has enough time in the spotlight to really last. They’re not only scripts, they’re pacing mechanisms for certain moods to come with your character. As someone who’s been known to spend whole campaigns with characters wrestling with the same internal struggles unless actively prompted out of them, the utility as a narrative pacing mechanism is something I so rarely encounter and I quite appreciate.

But.

When you finish a Quest, you get build points proportional to the length of the Quest, and power yourself up.

The capacity to write Quests and choose your own is a massive increase in authorial power, vs a lot of RPGs I’ve seen. The premise of Glitch also tends to lend itself away from concrete aspirations, and towards “I feel aimless and have no goal in life” as a thematically relevant point to the players, and thus a feature of play. And yet, it still gets compromised by this! Whenever a Chapter is nearing a close and someone’s Quests aren’t hit yet, they have to awkwardly shuffle through all of them to meet quota, or they fall slightly behind. The falling behind doesn’t actually mean much, but I’ve seen some pretty significant build point differentials build up, and even just on a player focus level – if they have the instrumental impulses I do, it scuttles nearly the whole operation. The Quest can’t even serve as a great signifier of how much more time should be spent dwelling on this particular beat, because they’re all trying to hurry through at the same pace.

Glitch is a better experience if you forget that you’re rewarded for completing Quests, and just use them as a neat narrative pacer. They’re genuinely quite good for that. But if you’re trying to win, they end up working against themselves. In trying to pull people like me into playing along with a narrative pacer, alongside other niceties (you get mechanical rewards for disappointing people, the exact sort of win-one-way-but-lose-another dilemma I was pondering above), the game instead makes it all the harder for me to set down my victory-drive and meet it on its own merits.

I think meeting on its own merits would be fun. I’ve had a lot of fun by doing that. Glitch is a solid game. And if I constrain my instrumental impulses to only when there is a mechanical or conceptual challenge to overcome, it can even work pretty well for that. But I can’t play all of it as efficiently as I can and get what the game wants me to get out of it.

If a [satisfying experience] is the win condition, then the winning move is to not try.

This is why I don’t like XP triggers, in PbtAs and the like. They’re written to direct players towards interesting actions in pursuit of instrumental goals – to try to get a player like me to move where I’m supposed to for a [satisfying experience]. And they can be quite cleverly written for that! But they just mean I rush through a quota really fast, and come out the other side without even having gotten what the game would have wanted for me. Yeah, I hit the right notes, but that wasn’t [winning] when I did it. It was just what I was doing to get the points.

You know?

The friends we made along the way

At the heart of RPGs, as they’re commonly conceptualized, is a paradox.

An RPG is a group improv exercise. It’s a many-vs-one competitive game. It’s a chance to explore characters in complex and fantastical worlds, see what they do, watch them overcome impossible odds. It’s a roll of the dice, and sometimes you lose.

“The goal of the game is to have fun” is a platitude. It’s irritating to me whenever I see it, and it doesn’t give me any direction to aim for.

But… it’s the only goal a lot of these games could have.

Remember the hypothetical instant-surrender adventuring party. What distinguishes a loss from a win, anyway? If the fight doesn’t stop you from moving towards the end of the adventure, why would you bother with it? If it does stop you from reaching the end – well, you stop playing either way, right? There’s no material difference outside the game, the only impact is that within the game, you get either a victory result, or a defeat result. Things get narrated differently, and if you don’t meet again, that’s all it’ll ever mean. Same as any game.

The paradox at the heart of RPGs is that they want you to care, but winning is the language they speak.

It doesn’t have to be. I highlight Quests not just because I really like them, but because they’re a method of game design that puts players in a seat where winning and losing, overcoming obstacles, doesn’t make sense as a description of what they do. Other parts of the game do put them in that seat, it’s not something like Microscope by any means, but you can’t play the act of writing Quests to win, beyond writing in the aesthetic beats you want to see happen – and that’s what you’re supposed to do. The only reason you can play following a Quest to win is that you get a reward once you hit its end.

But, I’m not talking about all the wonderful RPGs doing different things out there. I’m talking about the popular conception, where what you have as a player is your character and the ways they can overcome obstacles. That’s what you get handed, and it’s the primary path you have to influence the imagined world around you. That means that influencing it to become satisfied has to be a win, and not doing so has to be a loss. Right? What else could winning and losing be?

At the core of what I’ve discovered about myself with this post is – I like having the comfort of knowing that I’m doing it right. That I’m following a process as is expected of me, and whatever the result, at least I didn’t fundamentally misunderstand things. If I lost the fight, it’s because I zigged when I should have zagged, or the dice were mean to me, not because I should have just ran. This is why I favor mechanical structures over social ones in games – systems are much easier to read. I can read the rules and know how they go, but operating a human is a matter of understanding their mood and wishes and the social dynamic and that’s all very stressful. I can’t talk to a person and try to get them to see something my way and know I’m doing it right. I can only hope.

Instrumentalization is an approach to RPGs that lets you have that comfort. Here is a goal, here are the tools you have to work for that goal, use those tools and we’ll see if you’re up to the challenge. That’s where it comes from, for me.

Framing enjoyment as the end goal frustrates me because those aren’t the tools I have. I appreciate Quests because they, directly, are a tool for framing a satisfying narrative. They give me what I need to understand “hey, I think this kind of thing would be cool” as a goal to work towards. So I appreciate design like that, too, because I can read it and the way it signals me to act, and I know that I’m doing it right by following that.

When a game like Eureka gives me detailed combat mechanics and a stress resource to manage and skills to aim for rolling, and it tells me actual win condition is to experience a compelling narrative play out, there’s a mismatch. The reason for that mismatch is, the challenge is supposed to be a prompt. We play with the rules, watch the characters succeed or fail, and, with some distance as players, view the resulting shape with some satisfaction. Ideally.

I’m approaching games with the tools I’m given. If those tools are for overcoming obstacles, I’ll be playing the overcoming obstacles game. Whatever the shape is after the fact, that’s hard to prioritize in the moment.

I suppose, in some ways, it’s overly simple psychology, but I’m a straightforward woman. I think this is the mismatch that makes instrumentalization spring up where it isn’t “supposed to”. This is why it’s an observed phenomenon, and it keeps having to be denoted as either [what we’re not doing] or [what you must do to a minimum standard]. Gamism isn’t Narrativism. We don’t like flashlight droppers.

There might be an ideal band of instrumentalization to reach. There is, actually, it’s just not in the same spot from game to game. The important thing, though, is that RPGs are usually written with the assumption that you’re aiming for something else. You want a [satisfying experience] out of the game, out of the shape of a story it produces – how much that leads you to being efficient with your gameplay, well, that’s a bit of a non-sequitur, don’t you think?

I would like for more RPGs designed where the tools they hand the players match the responsibilities the players are trying to fulfill. I think that’s a good standard of design to work from, if you can. Until then, if you’re like me, I hope this read helped you to at least organize your thoughts. “The goal is to have fun” might bother you, like it does me, but it’s something people mean when they say it, even if it’s not much of an answer.

If you’re not like me, I hope this proved an interesting case study in the play psychology of someone with a very different approach. If you got this far, I appreciate the open-mindedness.

To be honest, I hadn’t expected this post to have gotten this personal. I was hoping to have wrapped all this up in a neat little bow and conclusion, but I don’t think I really have one, in all honesty. I’ve identified the source of why many games agitate me when I play them, but, I suppose I’ll have to be content to leave it at that.

So, yeah!

Good post. Much to consider.

LikeLike