The first RPG I ever played was D&D 3.5.

It wasn’t my introduction to RPGs. I knew full well what they were like. I had grown up around them, listening in on my family’s regular sessions. I had read a fair few! Or, at least, flipped through them. But, I had just turned 9, which was assessed as old enough to start learning how to play in my own right, and so my parents intentionally picked a relatively simple and straightforward game to get me properly inducted into the hobby.

(…For those of you taking notes at home, no, I would not describe D&D 3.5 as simple, nor straightforward. Nor a very good choice of first RPGs for someone new to the experience. But, so it goes.)

The game itself was an interesting time, though I’ll spare you a full recounting. There was a time paradox rewriting the world to insist that psionics had always been there, amusingly meta, and enough metaphysical puzzling to successfully induct me into, at least, that one table’s unique play expectations. Of course, I was hideously unoptimized and entirely unfamiliar with good play practices in multiple dimensions, so I can’t necessarily say I got the full 3.5 gameplay experience. But, that isn’t really what I want to talk about today either.

The process of making a character, in 3.5, is a rather strange one.

The game is distributed across a massive number of books. These books contain classes, races, feats, equipment options, monsters to face, there’s a lot. A character is composed of a race, which will modify their stats a little, a class, which will give them some powers each level (and be reliant on certain stats, so you need to pick a race to match), and then feats are a miscellaneous type of power they acquire at regular intervals, which might unlock new options based on their race or class (and have their own upgrade trees). Additionally, each level can be in a new class, rather than a preexisting one, and (though I didn’t parse that at the time) you get the most power by hybridizing a great many classes as dips together. “Prestige classes” exist as smaller packages of advancement and a focused concept, which you can spend your levels on instead of normal classes. Before getting into what these things even get you, and things like spell selection, there is a lot to pick here!

A lot to pick, and a lot of ground to cover. The process of making a character was one of reading a bunch of books and seeing what inspired me.

A lot did inspire me! In the Psionics book, there’s guys called Soulknives, who manifest the power of their mind into a knife and stab you with it. Promising, but their Base Attack Bonus scaling was a bit low for my tastes, so I ended up moving on. (At the time, I did want to engage with the gameplay and do my best in it. I just didn’t have the familiarity to do a very good job.) In the book of three weird analogues to wizards, there’s Shadowcasters, who have cool darkness magic they can focus on – aesthetically pleasing and pretty exciting. I’ll keep a note of that. Ooh, the book on dragons has people who magically bond with the form of a dragon and make breath weapon attacks – much like the Warlock from the Complete Arcane in gameplay, but with dragons instead of demons. Dragons are cooler, so that’s something to consider. Oh, here’s a cleric type dedicated to battling Illithids in particular – sun devotees fighting evil squid people who want to blot out the sun? Exciting! Oh, here’s the Book of Vile Dar- (my family did not let me read that one. This was a wise choice.)

The end result was relatively straightforward, after everything was flipped through. A half-dragon (since I enjoyed the draconic vibes enough after all) two-weapon ranger. Distinctly ineffective for the goal of making a mechanically powerful build, due to a lack of experience. Also rather lacking in characterization terms, since that wasn’t something I had the experience for, nor the focus – I was mostly considering instrumentally. (It’s what comes naturally to me.) But, I was satisfied, in a vacuum, with what I had gotten.

Recently, I built a character for Fabula Ultima.

Fabula is, on the surface, a lot like 3.5. …That might be a contentious claim, so, to narrow it a little – the character creation process is quite similar. The number of books is orders of magnitude smaller, but, you pick from multiple classes to compose together, informed by what stats you are good and bad at, and have the secondary dimension of somewhat-feat-like Heroic Skills to pick from as time goes on. Abilities can combo and unlock new options based on what classes you have unlocked, and there’s room to squeeze a lot more power out of your character by thinking through your class combos and planning ahead.

The options are no less heavy in implication, either. In the end, I had what appeared to be a singer riding a bike whose songs would physically damage all enemies in the area, and had a particular affinity over lightning powers. In both cases, I left the character creation with a clear vision of what my character looked like and how they would fight, if not how they were as a person – usually, those are things I dismiss as unimportant.

And yet, the two experiences were very different.

I’m not particularly attached to song-magic as an aesthetic. In fact, in play, I ended up leaning rather away from that angle for the fluff. But, I did select the song-magic class, the Chanter, as a core for my build. And, from then on, I selected options based on what would support that. Chanter powers are neither spells nor attacks, so a lot of damage bonus and modifier powers are inaccessible. The bike-rider class is one of the few exceptions, so I snagged that. Similarly, Esper, a class based on psionic powers, gives some strong damage buffs and support utility to cover allies, so I snagged that. The remainder was invested in powers to regenerate MP, something that both Chanter and Esper make good use of – I ended up part necromancer, part berserker, and with a dash of chaos magic, going from the premise of my character picks. I didn’t lean into those much at all, however. The concepts could be discarded, I was selecting for utilitarian reasons.

This build worked. Quite effectively, in fact! After the fact, when the GM reported our experience back to the dev, Chanter’s offensive capabilities were nerfed. (It’s supposed to be a support class, not a primary damage-dealer as I had used it.) I smugly take personal credit for that nerf. But, the important thing to note is – in those two hours as I was flipping through PDFs and noting down combinations, I was working towards a specific purpose. It was a satisfying optimization puzzle (though I don’t know if I’d say the same after, say, five campaigns’ worth).

3.5, for me, at age 9, was not that.

I did want it to be, in part. I did try to pick things that seemed to cohere. But I didn’t prioritize that over other interests, as I do today.

No, I was picking based on what struck me as cool. On what inspired me, on a conceptual level. I was reading through monsters, as much as player options. In a sense, the process of reading the rules became an aesthetic experience – character creation was just an excuse to be navigating through them and picking up the pieces. Seeing what compelled me, and taking the mechanics of that, to make it real.

From the mindset I had at the time, I think what I did in Fabula would seem quite alien. Not the process itself, nor the focus on optimization – like I said, I wanted to do that, even back then. But how I treated the result.

I had here a singer. An Esper. A dabbler in death and chaos magic, apparently! And I had dismissed the implications of all of that. In play, I framed her as a sort of tinkerer, cobbling together mechanical devices to produce sonic attacks. Yet, I hadn’t even touched the classes that leaned into that sort of crafter concept. Instead, I’d taken many choices that had strong character implications, and ignored them as I saw fit.

If, facing 3.5 at 9, I had ignored those implications much the same, I think I might have done a slightly better job at optimization. Perhaps not, 3.5 is notoriously impenetrable on that front, by design. But the thing is, there’s no way I could ever have done that. I wouldn’t have ignored the meaning of the options I picked, even if I was informed I could.

They were the main reason I was here.

Fluff

My inroad to the online RPG community was Pokemon Tabletop United.

PTU is, quite frankly, not a good game. It tries to make an interesting grid combat system, and ends up with a relatively rote damage race. The trainer options that let the human fight alongside their pokemon massively outclass any player who doesn’t pick one of their own. There are almost no reasons to ever take an action that isn’t just launching an attack. Any pokemon build that isn’t a durable one-stat-focused damage dealer is sabotaging itself. The noncombat skill roll math is horrendous. The character options are littered with accidental “trap options”, choices that are a complete waste if you do pick them.

Despite all that, funnily enough, it is one of the better pokemon RPGs you can find out there. Fandom RPGs in general are a space riddled with terrible design, sad to say. Each with their own character, interestingly enough. Fire Emblem fan RPGs are almost always dedicated to tactical grid combat, by way of replicating video game math and mechanics unchanged (a terrible choice for a tabletop game, especially when each player only gets one unit to control). RWBY fan RPGs tend to play in a distantly-rules-lite space, yielding very rote back-and-forth combat for a story that is (as I distantly understand it) most notable for stylish fights. It’s a tragically consistent rule of thumb that a fanmade RPG for a given story will always be a bad choice.

Of course, there’s obvious reasons for that. Most of the people who would make a fan RPG for a story they like are young, inexperienced with RPG design, and primarily concerned with replicating the contents of the story that they’re a fan of. They want to design an RPG that can contain the things they liked. And, from that standard, all of the fan RPGs I’ve read do succeed. PTU can, in fact, contain pokemon battles. The gameplay of them is very rote, but, it has them. It has a styler item in its list of items, so it can technically contain the events of the Pokemon Ranger spinoff. And, if you approach the game with a strong appreciation for Pokemon as a series, your passion for that can carry you to a good experience, despite the game itself not supporting much of anything at all. The game serves the purpose of listing things that you can recognize, and then you the players are pleased by that recognition.

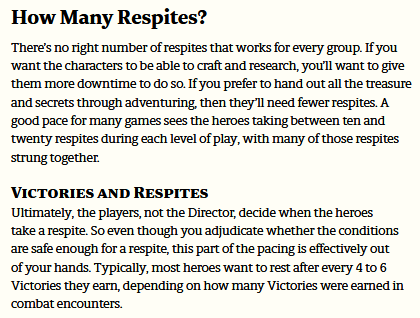

It’s the context of PTU‘s community where I first heard the adage [fluff is free]. Among PTU‘s classes is the Taskmaster, presented as such:

It’s a class about pushing your pokemon for power, applying Injuries and fatigue in return for some fairly sizable buffs. The text blurb does comment on it being a way to represent mistreatment, but also other demanding training styles. Much of the time, however, it gets discussed in a far worse light. A common attitude among newcomers to the community is that the class is intended to be evil-only, and players shouldn’t be allowed its options at all (or should be judged for taking them). This attitude would be silly in any context, but made worse by the fact that Taskmaster is genuinely a quite solid class, a powerful option that players would plausibly want to take. “Fluff is free”, then, gets invoked in response. One can take Taskmaster for its powers without it implying abuse. It says so right there, but also, it doesn’t have to imply anything at all. (Much like my Necromancer investment back in Fabula.) You could take Taskmaster because your pokemon just push themselves harder on their own right, if you really felt the need for something. You certainly don’t need to give every NPC who’s portrayed as abusive some Taskmaster powers. These are game elements, serving a mechanical purpose, and the more you arbitrarily tie assumptions to that, the worse the game gets.

This is true. PTU gets worse the more you constrain concepts to build choices. It’s not a very good game, and there’s some specific bounds you can stay in to make it relatively decent – binding concepts like that moves you extremely outside of those bounds. There is a not-very-useful class called Researcher. You should be allowed to play someone who is framed as a researcher without investing one of your class slots into a waste. For gameplay, and thus for a compelling RPG experience, this is a straightforwardly correct piece of advice.

However, there is a discrepancy here. There’s a distinction in mindset. The logic behind fandom RPG design isn’t constrained to its designers – it’s usually also what the players expect. (Or, at least, readers.) They want a game that can contain and represent everything they expect out of the story they’re used to. The Taskmaster, from that lens, is one of the only ways to represent a trainer who’s abusive towards their pokemon. Since that’s an expected trait in parts of the world, specifically to be depicted as a characteristic of villains (since, discourse aside, pokemon as a series generally considers animal abuse to be a bad thing), why shouldn’t the enemies be given that class? Why should a player be allowed to pick the option used to represent abusive training, when a more palatable form could find a different representative in, say, Ace Trainer? When you’re looking at rules as a matter of representation, the logic is sound. And, “it makes the game worse” may or may not be an acceptable answer, but more importantly it’s a non sequitur. Whether the game is good or not isn’t the point.

This is the mindset difference. This is what I had at age 9 that I don’t have now. The focus on rules as representations, and primarily being interested in what they represent. When I settled on a half-dragon, their big strength buff made me look for a class that would be making use of strength, but I picked it because being a half-dragon is cool. If they didn’t have the strength bonus, that wouldn’t have stopped me from picking it. Maybe I would have gone for a class focused on a different stat, but I still would have played a half-dragon – because being a half-dragon is cool.

“Fluff is free”. The claim of that statement is interestingly layered. Argument one: you can separate a given option into its gameplay function, and its aesthetics. Argument two: you can replace the aesthetics, and, as long as you preserve the gameplay function, the option has not been meaningfully modified or compromised. In other words – sure, being a half-dragon is cool. But you can take any other option, change its aesthetics to read “I am a half-dragon”, and it won’t cause a problem. There’s no reason that taking this one mechanical option should be a requirement to say that. There’s no reason you have to give someone Taskmaster powers to represent an abusive trainer. That’s the ideological thrust of the argument. It’s a direct challenge to the mindset of my young self. It helped me quite a bit to move past it.

Then again… would I have even made a half-dragon, if I hadn’t read the option?

I have a complicated relationship with the concept of imagination. We’ve come to an understanding, in recent years, but it’s still a bit of a struggle for me. I work best with concepts, prompts, constraints – something to anchor myself to, and work from. I have a distinct memory, at one point in school, of being given an assignment to just write something. Anything. We were all sat there for half an hour, in front of a blank page. I could not think of anything. It was very distressing, especially as someone who considers herself a rather creative person! I willfully encoded the memory as something to never repeat again – made a point to always have something in my head to write about, if I had to. It’s a very distressing experience, to be in a complete conceptual void. Nothing to start from, nothing to think.

That assignment was in primary school. Actually, reviewing my memories, right around the time I was first being inducted into RPGs! These things align quite well. One of the big things I appreciated, reading through all those 3.5 books, was all the ideas they had for me. All the concepts I could imagine, and then compose. Everything it predefined for the world, and promised a context where it all existed.

I played a half-dragon because half-dragons are cool. I had the thought “half-dragons are cool, I should play one” because there was a book on dragons and why they’re cool, and an option to play a half-dragon right there in the Monster Manual. If those hadn’t been there, I don’t think I can confidently say that I would have gone, “hey, what if I play the child of a dragon?”

I mean, I might have! The dragons are a whole third of the title of the game. (Giving “and” equal billing with the other two is perhaps overly generous.) But there were plenty of concepts the books presented to me that were compelling in their own right, and finding those compelling concepts was a core part of what hooked me on reading the game at all. Why would I have run, say, a deep gnome that gets refluffed as a half-dragon, when I could be going back to that soulknife idea and pondering the personal implications of the Elan? (A concept that, in retrospect, offered me some light gender implications.)

This is cool, right? It’s compelling! And it gives me a basis to work from, in a way that a blank page never does! If the Elans hadn’t been in the book, would I have thought to refluff something as that? Probably not! Nowadays, with a lot more experience under my belt, I think I could… but that’s in no small part because I’ve already been exposed to the Elans themselves. The idea is in my head, and now I have that idea to work from. Now, I have enough of a wealth of media experience and ideas that I can, when faced with a blank page, make up some sufficiently-complex fluff of my own. But that is a skill and an accumulation over time. When I was first sitting down to this, I didn’t have that. If the game had assumed I did, and relied on that… I wouldn’t have done well at all.

But you can split them

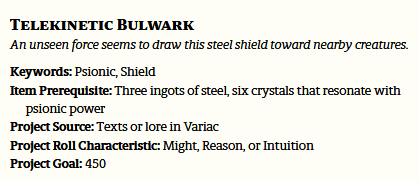

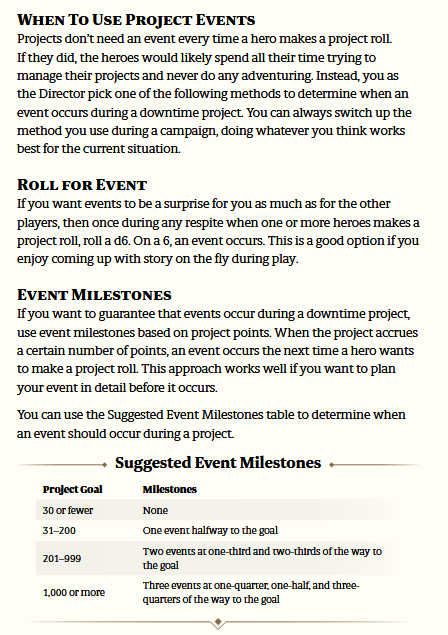

Note what I just posted.

That is fluff. Lore, if you will. It’s a concept. A cool concept, but, still, just that. Here, on the next page, is what I didn’t post:

You know. The actual rules on how to play an Elan. The stuff that makes all that not just a bunch of cool ideas.

And, I split them up. Easy as pie.

What’s there to stop me from using the lore blurb of Elans, but with a different race option for the rules? I’d certainly appreciate that if I wanted to play a charisma-based class, that’s for certain. Or any class, really – not getting a single bonus is pretty rough. Or, if I was really attached to the Naturally Psionic power for whatever reason (to my understanding of the game now, I’m pretty sure Elans are a terrible build choice), why shouldn’t I be able to use these rules, but conceptually I’m playing as a dwarf? Or, say, a half-dragon?

Or, in more abstract terms – what difference would it make if, instead of this arrangement, they entirely separated these things out? A section of lore concepts for various peoples of the world, and then a disconnected section of various mechanical packages you could pick. Pick a package, pick which concept you would like, go from there. What, if anything, is changed by the separation?

Interestingly, here, present-me actually has more to say than past-me. My younger self did try to read through lore sections. She wasn’t all that attentive, but some bits stuck out. Her focus was on the parts where there were rules, but it was only a focus.

I, however, will entirely skip a lore section unless there’s a reason I need to read it.

In time, frankly, I’ve grown rather callous to cool worldbuilding. It’s nice when it’s there, and I enjoy coming across it, but primarily I enjoy encountering it in play – worrying about it in advance and presenting it in an understandable form is there for the GM, not for me. And, indeed, I take this to heart when I do GM. There, I do need to read up on the world and what it is, and then present the important parts to the players to absorb. But, as a GM, I’m not looking for inspiration, I’m looking for tools. And, as a player, the rules are my tools. If I can’t use those, the game isn’t doing its job. A designated lore section is free for me to skip.

If I’m starved for ideas, I do loosen up a little. Which is why past-me was more open to it. But, only a little. Ultimately, an ungrounded concept just doesn’t hold much meaning for me. Every example of game lore I can think of that I do appreciate, I’ve appreciated because it comes up as a meaningful factor in the gameplay. When reading a lore section, I can’t know what that’s going to be – but I certainly can once I start playing the game, and the GM presents me with what we’re dealing with. Before that point, in the character creation phase back here, all I’m looking for is “being a half-dragon is cool”. I might not have made it to the end of the list of potential race concepts before finding one I like and just taking that, if there hadn’t been a meaningful difference. Considering how many sourcebooks I hadn’t read in detail before I locked it in, I arguably hadn’t.

But, these are personal quirks. There’s plenty of people who read lore sections more thoroughly than I. That it wouldn’t work for me in particular is only so notable, especially when it would, to some degree, still work.

Here’s a better question.

If they had been separated like this, who on earth would write “you get 2 extra power points per day and can spend one to skip all needs for food and water” as a package, unconnected to any fluff?

This doesn’t read to me like a terribly good option. If I were selecting things devoid of context, I definitely wouldn’t go for it. More importantly, I don’t think the option would exist at all, without mechanical reason to take it over the other choices, if they were just presented as contextless mechanics. And, as a contextless mechanic, “you can channel psionic power to specifically avoid the assumed baseline bodily needs of a person” is just very strange to think of.

The reason for that, of course, is it’s informed by the fluff. It’s there to enforce it, to reify it. Elans have transformed themselves into something notionally immortal. Hence, they can channel their innate powers into being immune to a natural death. They have those innate powers because the ritual to reform them is a psionic awakening. Discarding their old humanity makes them hit the uncanny valley, so they have a charisma penalty and count as Aberrations. Each of these mechanical elements is contextualized and informed by the fluff they’re attached to.

Without that, this is a jumbled mess that probably isn’t worth giving a second glance, in comparison to any of the better options. With that… mechanically, it is still a jumbled mess, but it’s serving double duty.

The lore blurb tells us what Elans are like. The mechanics emphasize certain of those traits. Elans can last forever without starving, in theory. Here’s the power that makes that mechanically real. Elans have shed their humanity for the sake of a superior form – here’s the penalty for having separated yourself from that old personhood. The presence of these mechanics is there to underscore and bolster the fluff. These rules are here to say, “no, I mean it, Elans truly are immortal and ageless. Watch.”

It’s the same design logic as a fandom RPG, just, without a preexisting fandom. The rules are made to define that this thing exists, and these aspects of it are meaningful enough to be given rules. Meaningful enough to be made true, in the language of truth – game mechanics.

This is what I call designing for the “tactile appeal”. A rule is solid. It’s tangible. Something that doesn’t connect to rules is, well, fluffy. Easy to tear away, put something new in its place. Ephemeral. If Elans were notionally immortal, but one got trapped in a cave and the rules gave them no defense against starvation, it would feel hollow. That might not be likely to happen, but this rule draws our eye to it. We imagine a circumstance where the rule might matter, because it’s there. Rules can solidify a concept. Here, the rules have solidified the enduring power of the Elan. It’s true, now. Truer than any lore blurb could have persuaded us it was.

It’s a tactile appeal because the rules are tangible. You can look at them, you can bounce of them, you can be denied by them. The appeal of tactility is that sense of a tangible thing, telling you what is real.

Meaning and Importance

Towards the end of my post on the Ghost Engine, I proposed two related concepts: meaning, and importance. Something is meaningful in a game when it matters to the players on an emotional or practical level, and important when it is a tangible element to the rules and can’t be modified without shifting the shape and resulting consequences of the system. Design for the tactile appeal, the fandom RPG perspective, is driven by the initially-intuitive goal to align the two. Players tend to be dissatisfied when these things misalign. So, if you make mechanics that reflect anything the players might view as meaningful, then you automatically make them important as well. In theory, at least. You give them the feeling of importance. The sense that changing them is messing with the rules, something tangible.

That’s one of a few reasons why “fluff is free” gets so much pushback. It highlights the ways in which this alignment is an illusion. Elan agelessness has rules to it. Does it matter to most of the game if you change that, slap the appearance of an Elan onto the mechanics of an orc? Not really, but by doing so, you lose the comfort of a tangible rule to push against. You can no longer say “the rules say I’m ageless”, and, more importantly, you can no longer say “it matters that the rules say I’m ageless but not you”. Of course, you still can, by adhering strictly to whatever mechanics people do choose to take, but now there’s an active misalignment between who is, in story, supposed to be ageless, and who actually is. There’s a discrepancy between the meaning people expect, and the importance the game constructs.

Games are, among other things, a form of communication. All art is. More specifically, RPGs need to communicate to the readers how to play them. The book describes an engine, constructs all the pieces and the methods to operate it, but it can only be a manual. The readers have to know how to navigate it, and follow the flags. They’re blind ghosts, trying to imagine the device they’re flying through. To do that, the book really needs to convey the shape of that device.

A game rule is thus a method of communication. By mechanically reifying something, it’s signaled to be important. Thus, the intuition offers, it should also be meaningful. Sometimes, this is wrong. Sometimes, game rules don’t even accurately represent importance, let alone meaning! It probably does not matter at all that Elans can spend some of their power to not need to eat. 3.5 does not have much by way of tight survival mechanics. Worrying about starvation isn’t where the game is centered. If you have that game knowledge, this power is probably so unremarkable that it’s a wonder I’ve spent this long talking about it. If you don’t, and you happen to read it as a flag, you might take it to be both meaningful and important – when in practice, it’s mostly neither. In the worst case, you might see it as cause to try to play harder into 3.5 as a starvation survival game, only to learn your gameplay plan has reduced to a spell slot tax on the party Cleric and nothing more than that.

Frankly speaking, the logic of alignment is immature. Meaning is a personal, interpersonal, and emotional reaction spawned by humans interacting with a system. Importance is a matter of system design done well in advance, impossible for the developers to edit by the point it hits the table. Expecting everything meaningful to be important is maybe an intuitive expectation, it certainly made sense to me as a child, but it simply does not produce a good game. D&D 3.5 does not play very well. You can spend months reading up on how to constrain player options to a band of balance, and the result will be, at best, fine. PTU does not play very well, in much the same way. Shadowrun‘s large gear-juggling tables, Vampire‘s detailed selection of what sorts of supernatural powers given bloodlines can give you… these things have all, in my experience, been much fun to read through and imagine, and appreciate the tactility of being able to select and combine options, and not one of them has made for a gameplay experience I would describe as any good. Considering I can, instead, peruse the catalogue in Lancer, and then actually have a game on top that works well? Designing for the tactile appeal first can only ever in my eyes be a mistake.

But, even with my prejudices, it’s an interesting mistake. It speaks to what people tend to expect out of game systems, what they want out of them. [Being tangible] is a desirable quality. It makes something feel more real. That’s something a rule can do, entirely independent of what the rule actually is! The shape of the rule will, over time, define how people interact with it, but the presence of the rule in the first place makes it more real. Or, at least, makes it read that way.

I often think of RPGs as an augmentory artform. There is an underlying baseline of freeform roleplay, as one might find in a forum or text chat online, and then the rules interpose and reshape how that experience goes. As it so happens, this is an anachronistic perspective. Freeform roleplay, as we see it now, distinctly evolved only with the internet, and evolved out of the preexisting RPG spaces – freeform evolved from systematized play, as strange as that seems. However, it’s still a useful model. (For some systems better than others. Some games I will classify the gameplay experience as “augmented freeform roleplay” straight-up, others are a lot more structured.) When looking at a system as an augmentation, the core question is, what does it provide to make the experience better than just doing freeform? Naturally, I move towards answers like, this makes for an engaging tactical experience, this produces interesting narrative structures that wouldn’t manifest easily just from freeform play, etcetera. But, the tactile appeal is the first intuitive answer here, as well. In freeform play, everything is fluff. Being able to lift up a part of the world and say, “this is real,” and have some deeper weight behind it than just your own narrative authority, there’s a satisfaction to it! In some freeform roleplay spaces, new systems are developed to be layered on top for exactly that purpose!

The tactile sensation of engaging with rules, and having them reify what you care about, is one of the simplest ways to enjoy RPGs as a medium. It’s very intuitive, and it connects concepts rather easily. It worked for me as a literal child, and it can work for, I think, pretty much everyone.

But, as a core of design logic, what it produces is, at best, a toybox. A set of solid rule-objects that you pick up on your own, appreciate their solidity, and then don’t worry about how they actually connect. The result can only ever make a decent game by happenstance, coincidence, and, usually, a lot of work and effort on the part of the players to redesign it into something actually functional.

I do think, even for better design philosophies, it’s a power that can be tapped into. It’s the source of a lot of juice in a content roster. If you can make well-designed, interesting ideas, and have that inform how the mechanics work, then you get a content roster that’s a lot more exciting than just a bunch of numerical bonuses to string together! In a sense, every good PbtA game has a core of the tactile appeal of, this playbook reifies this cool character archetype you’re imagining. (And, similarly, it can inspire people who wouldn’t have thought of that character archetype, if they then see it presented to them.) Failing to land the tactile appeal is what makes for juiceless powers, and failing to ground the powers in an understandable aesthetic can lead to something feeling distant and a bit too blank-veneer-game-y. I don’t mind that sort of thing, but I know people who do. Understanding the tactile appeal, figuring out how to resonate fluff and mechanics, is the key to solving that.

But that can’t be the underlying core of your game. Not if you actually want a game. Not if you want meaningfully augmented freeform roleplay.

As a 9 year old, I was happy to flip through a toybox.

But even then, the gameplay wasn’t great.