I’ve been having an interesting time with Draw Steel recently.

At the start of 2023, Dungeons & Dragons’ new Open Gaming License was released, and people got upset. The history of the OGL and what it has meant for RPGs as a scene is a very long one to enumerate here, and is honestly centered more on the d20 boom era than it is now, but, sufficeth to say – at the time, there was a lot of badwill towards WotC that emerged in the massive D&D fan scene, and an interest in moving to new RPGs. This represented a significant audience to capitalize on. Not an audience for indie RPGs per se, as some people optimistically predicted. But, rather, a group of people with a lot of interest in a game like D&D, with enough serial numbers filed off and the money not ending up back in WotC’s corporate pockets. Which, fair enough, honestly. I’m an advocate of ‘alternative acquisition methods’ in circumstances like that, but whatever works.

In response to this news, many projects were announced offering just that. The D&D 5e experience, but without the same evil corporation behind it, and perhaps with design decisions you favor. At the time, I called these efforts ‘Paizo hopefuls’, since this was the path to success that Pathfinder rode back in the reactionary response to D&D 4e (and, interestingly enough, another effort to tighten up the OGL at the time). I predicted, somewhat pessimistically, that these were mostly misreads of the situation – there wasn’t the same window of opportunity that Pathfinder had here, because everyone already knew the trick and multiple people were jockeying for the same position.

I would say, in terms of how many names were bandied around at the time that have fallen relatively silent since, I was somewhat right. But I definitely underestimated the impact of having a prior significant audience base to sell to. Both Critical Role and MCDM have made their own Paizo hopeful successes, selling a mechanical framework that promises to offer the D&D experience, and those games have seen relatively solid success. Respectively, those are Daggerheart and Draw Steel.

All that to say that a lot of my complaints regarding Draw Steel can be traced back to complaints I have with the gameplay of D&D, and in retrospect it is very predictable that I ended up with rather a lot of them. And, similarly, most answers to the question “why was this designed this way?” will end up tracing back to an element of D&D 5e, either in gameplay format or in play culture.

Draw Steel in particular takes a lot from 4e as well. Its combat system is well-elaborated, with clearly defined powers and movement on a grid and such like. It’s a pretty good combat system, as tactical games go. That’s what drew me to it, really, and on that front it hasn’t disappointed much. In terms of games I would recommend looking at just to get a taste of the combat, it’s on that list!

Alongside the combat formula, it takes the overarching inter-fight attrition format from 4e. Everyone comes with a set number of heals, called Recoveries for this game, that get spent when they heal between fights or are targeted with a healing power. Once they run out, they can’t do any more, until they take a proper rest. There is a notional push-your-luck system at play, too – the more fights you play in sequence, the stronger you are at the start of each fight. The idea there is that, once you run out of heals, you might still want to push through a fight or two, relying on alpha strikes to carry you a bit further before you have to rest.

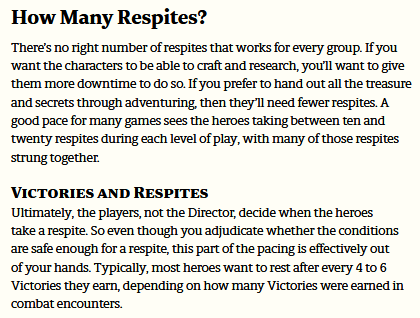

That sort of setup works best when resting is a difficult decision. And the game does suggest that the GM impose a punishment on rests, in the vein of “time has advanced so the enemies are now doing a new bad thing,” so the attrition can come up at all. (Otherwise, it would be best to just rest after every single fight, and it would be nigh-impossible to blow your full heal budget in one fight. That’s a hazard of letting players set the pace for these things.) This gives some variance in how many fights can happen between each rest, but the expected amount is (to my understanding) roughly 4-6 Victories’ worth. Difficult fights give two Victories, and sometimes the GM might give them out for accomplishments that don’t take a fight at all, so that isn’t as much as it seems. If anything, it’s comparable to or only slightly longer than Lancer‘s 3-4 fights between each rest, and the fights aren’t as tough as Lancer‘s unless they’re the notably difficult ones. So, it works out as a pace.

The standard progression pace goes from levels 1 to 10, and costs you 15 Victories to earn a new level. (Victories were secretly just the XP mechanic, which makes sense.) If you follow the standard pace of rests, and don’t push your luck to the point of getting in the 7-8 range before resting (which is doable!) you end up hitting 3 rests each level, or 30 over the course of a full 1-10 campaign.

…Which is a pretty useless number in isolation. Neat, I suppose? Why am I bringing this up?

Well, it turns out, rests aren’t just resets. They’re long-term progress. (This is, of course, another finger on the scale towards incentivizing resting after every fight. Which would remove any combat tension. The GM will have to work mighty hard to ensure that’s properly disincentivized.) During each rest, you can work on a long-term downtime project, and get something from that! This covers crafting, training, building something useful in the world, getting some buffs that last until the next time you rest, and a few other options. This isn’t unheard-of by a long shot. The aforementioned Lancer does something much the same. This is just a bit longer-term, since campaigns are gonna be a lot longer. Plus, the mention of crafting caught my eye in particular. As with D&D, this game has magic items as a significant source of power, as well as build differentiation. In D&D proper, those are essentially handed out by the GM at their leisure. Having a player-facing crafting system gives me as a player the chance to work towards the things I specifically want for my build, rather than relying on fiat! That’s quite appreciated.

There are a few factors that determine how much progress you get on a given project each rest. The base roll is 2d10 plus a relevant stat, with stats ranging from -1 to +5. (It is technically possible to break this cap at the very endgame, reaching +6 in one stat.) At the start of the game, your highest stat will be +2. If you have a skill you can apply, subject to GM approval, you get another +2. If you don’t have the relevant language, you get a -4 penalty, and for some projects, you get a -2 even if you do have the relevant language. At level 1, in optimal conditions, you get 2d10 + 4, and at level 10 in optimal conditions you get 2d10 + 7. If you don’t have the language, something relatively common to encounter, you get 2d10 + 3 at level 10 in otherwise optimal conditions. Often, you can’t roll your best stat, or you might not have a skill that applies. Also, there’s a crit chance, but the chance is 3/100, which is depressingly rare, and that means over the course of 30 rests in a game, your expected value doesn’t even hit seeing it once.

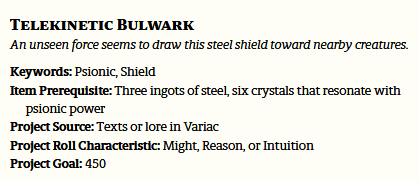

That’s a lot to juggle, but the numbers are pretty tightly bound. Since a full statistical analysis here would be pretty overkill and also include a lot of assumptions anyway, I’ll just go with – if you take 2d10 + 4 as a good benchmark for the roll people expect as they try projects they’re better and worse at, you get around 15 points per rest. That’s a good number to work with. Over the course of a campaign’s 30 rests, that gets us a cool 450 points. Nice!

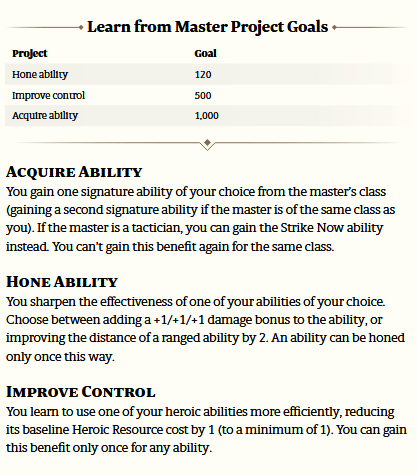

How much can that buy us?

…Well, certainly not that. This is the first downtime project in the book, and it sets a pretty stark impression in terms of numbers. If people forgo their own progression to contribute to someone else’s project, something they can do (but that makes it more likely they end up having to roll worse numbers, of course), then it would take the entire budget of 7 PCs working all campaign on this and nothing else to get it done, right near the end of the campaign. Frankly speaking, I don’t think running this game for 7 people would be a good idea! A lot of things would break first. So, that’s essentially unobtainable, per this setup.

They aren’t all so bad. This one is unobtainable without help for the new ability or the discount, but you can get a damage buff to 3 different abilities over the course of a campaign and still have 90 points to spare (which can’t get you much, but can get you some miscellaneous narrative benefits). It’ll take you 8 rests to get to around 120 points, so you should get the first buff in just before the final push of level 3.

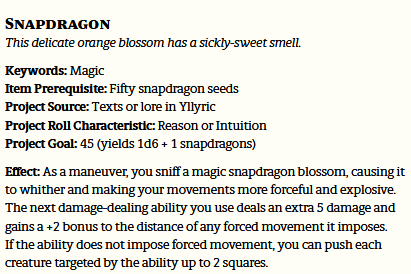

You can get a handful of consumables for only 3 rests! That’s just one level. Though, they do get more costly as they hit higher-tier consumables – the beefier ones are 180 points for a set, or more.

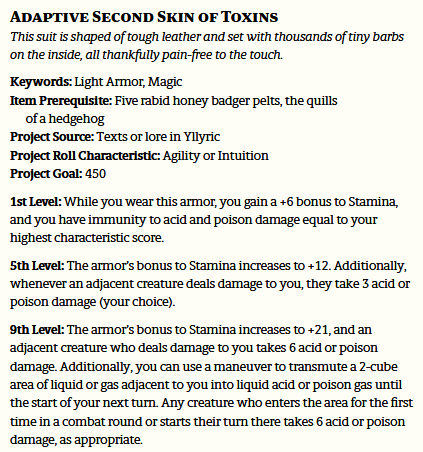

Most importantly, here’s the big one. A magic item. You have slots for three of these things, and they scale your damage or health quite significantly for the first two. And they cost… 450 points. Your entire budget. Sneaking in at the last rest of the campaign, after everything is said and done. You would need three times that to fill up your slots properly – and then there are lesser magic items you might want to craft, starting at 150 points and going from there.

This economy is in shambles. What on earth is going on here?

Everything is made up and the points don’t matter

There are ways to punch up your numbers.

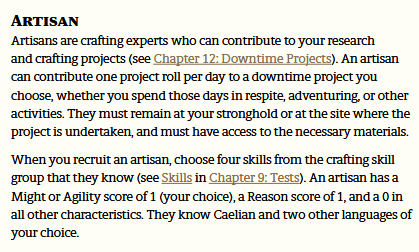

This is pretty notable! You spend one rest recruiting a guy, and for the rest of the game, they roll on a project you set for them. Not as well as you, if the stars align with their skill, language, and relevant stat, they only roll 2d10 + 3, but you probably pick them for a specific reason, so let’s be generous and still give them the 15 benchmark per rest. One rest spent at the end of level 3 gives you 21 more, another at the end of level 6 gives you 12 more, another at the end of level 9 gives you 3 more. 33 net gained rests – that more than doubles our output! Which means, by the very end of the game, you can hit 2 out of 3 magic items, and you can get your first one by… two-thirds of the way through level 7, at idealized pace. (And that has your first two guys optimized for the first project, which means you might need to spend an action to get new ones for the second one.) So, still near the end of the campaign. And, followers aren’t necessarily forced to be crafters. You can take them as an additional fighter in combat, and that’s pretty dang significant.

That all assumes, of course, the GM decides to hand out Renown consistently. As it says, “in most campaigns, the Directer sets the characters up to earn 1 Renown per level.” If the GM doesn’t do that? If they decide a given opportunity for glory was squandered, or even they just forget to? That’s a rough reduction, and even if this is followed to the letter, with the GM not exercising any of the power the game is offering to them, you go through most of the game without getting anywhere if you aim for the meaningful investment.

What else can you do? Well, the GM can just hand out bonus points as a loot reward, and some of the backgrounds give a starting budget of bonus points. They get these instead of a language, so it does reduce the numbers they’ll be able to roll during project rolls to compensate – each one is a -4 per applicable roll. I believe the lump sum works out better than taking the language, for these numbers, but it’s something.

And finally…

Turns out these numbers were totally off all along. Somehow, you’re expected 10-20 rests per level. Despite only fitting 3 into the number of fights necessary for an adventure. So, all that math was entirely wasted, and, if we average 10-20 to 15 per level, that’s 2,250 points over a campaign, before considering the Renown bonuses. Much more manageable. So, case closed, right?

Well, if you’re the GM in the game I’m in, no, case very much not closed. Specifically, with the reaction of “I would absolutely not expect people to just toss a bunch of rests in a row at the end of a level to meet quota, that sounds like exactly the sort of thing I was supposed to be nipping in the bud with narrative threats.”

And, it does say even in the snippet there. It’s the Director’s choice how that pacing works out. It’s their choice how many rests to allow before throwing a new problem at you to make you go out and deal with it again. It’s their choice if they give you bonus points, or Renown, or whatever else you need to make pace. The only amount the system guarantees you is what you can earn from the rests you need to do during an adventure.

And it doesn’t even do that, really. See, you can get the points – but actually working on a project isn’t that simple.

Here’s an item I’m planning on getting for my PC in that game. It’s a major magic item, its goal is 450 points, as expected. It’s got some keywords, it’s got a name, it has the stats you can use to roll on it. And it also has two other lines. A source and a prerequisite set of items.

You can’t start a project until you acquire those.

How do you do that? Ask the GM.

Is steel probably around? Yeah, I suppose. Crystals that resonate with psionic power? How rare are those? How obscure are the texts describing the item?

Ask the GM.

If you’re the GM – it’s entirely up to you. Want to hand them out for free, because they can probably find them? Want to make them bargain for it? Want to send them on a whole dungeon delve to get them? The power is in your hands, and the guidance is just “whatever you feel like.”

(And, of course – unless the players proactively tell you which specific items they’re interested in, you have to consider giving this out for every item on the list. And there’s a lot of them!)

At the start of the game, it’s plausible to not have the requirements for any of the long-term progression options. And if you don’t, you’re stuck investing in some miscellaneous temporary buffs or narrative bonuses, and losing progress that long-term is pretty tight unless the GM actively chooses to loosen it for you.

And then, halfway through the project, you can get hit with this:

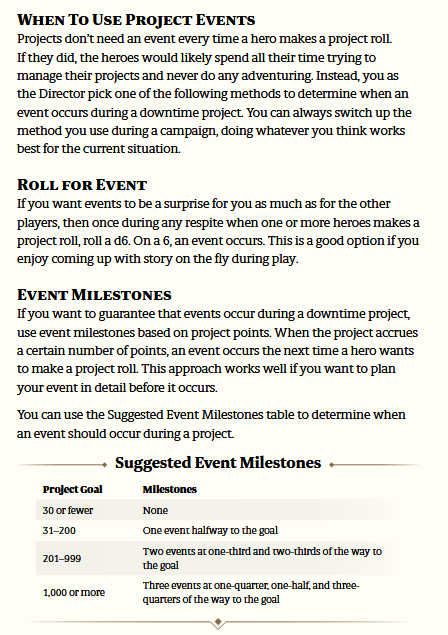

This is a bit of tech I really like from The Treacherous Turn. Completion stops. At certain points in a progress bar, you hit a roadblock, and have to go acquire a piece of data to resolve it. In TTT, it fits the bill of being a rogue AI that thinks weirdly and needs esoteric data to perfectly predict and control the world. It also helps that you have a lot of progress bars to work on at a time, and the resource-management of those projects is the gameplay. Here, events are rolled on a table, and sometimes they’re free rolls (ie a small bonus to progress), but sometimes they serve as a completion stop proper. A thief came in and stole the project source – go on an adventure to hunt them down, and you can’t continue until you do. The GM is free to choose whatever effect they want, to – if they want to stop your project, they can.

In other words, the GM controls how fast the projects go, if you’re allowed to start them, if you’re allowed to continue them – the only thing that’s not explicitly under their control is what options exist to be conceptualized as projects in the first place. And that’s easily done implicitly – just don’t hand out the requirement in the first place.

If you take this subsystem at its base, without the GM handing anything to you, you can’t get anywhere meaningful. 450 points all campaign, and who knows when you’ll be allowed to even start. If the GM does hand anything to you, they have a lot of control to define however much they’re handing to you, when and how you can get anything out of it, and what you’re even allowed to get in the first place.

This subsystem has circled to right back where it started. If the GM feels like it, they give you the item you want as loot. If they don’t, they don’t. You have no control.

Which brings me to this quote from myself earlier in this very post. This was my initial assessment of the subsystem – excitement and relief, that I had a system to rely on instead of GM fiat. I only realized I’d been deceived once I saw it in action and ran the numbers myself.

Who calls the shots?

I like rules.

I like them for a lot of reasons. But, as a player, I like rules as a source of power. Rules are tangible, solid, and invocable. I can point at the text and say “this happens, because of that,” and be demonstrably either right or wrong. That’s a consistency I don’t get in real life – and it’s extra valuable in what is ultimately a social situation containing people I may or may not trust or know all that well. When I’m a player, and there’s a GM with the authority to declare whatever they want and veto whatever I propose, having a rulebook that I can cite to push their hand back to what is the correct structure of how things are supposed to work is nice. It means I’m not entirely powerless, you see what I mean?

That’s one of the reasons I enjoy tactical games. And, in its combat, Draw Steel is solid for that. Its rules are clear both playerside and enemyside, and I can respond precisely to everything the GM offers – including correcting them. It’s a solidly structured ruleset that defines how I can engage with its tools, and gives answers that the GM is at least expected to innately accept.

The crafting system, despite looking like that on first blush, is not that. It is designed on every level to ensure the GM maintains veto power, in a variety of forms – and, in fact, the default form is a veto, due to the pacing. The numbers simply do not work, unless the GM willingly allows for and opts into providing bonuses of one form or another.

That’s the core of the above rant. I expected the crafting system to be meaningfully structured and codified in a way that I could use without augmentation, and the GM could rely on leaving it to the players to do the same. The numbers do not work out like that, and that means I am unsatisfied. It does not do what I wanted or expected it to do.

…What about the fights, though?

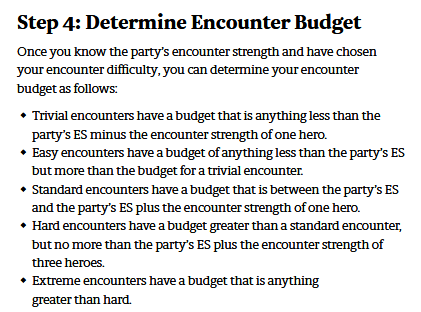

Sure, I can say the GM is expected to just accept what the rules say for them. But that’s within the context of the fray. When they’re setting up a fight, what stops them from making a map with a pit the melee guys can’t cross over and enemies that sky kite and launch attacks from above? For that matter, what stops them from ignoring the encounter budgeting rules and just tossing so many enemies at us that we instalose?

…Not the actual encounter building rules, it turns out! The budgets are fairly sizable bands to work within, and the GM is fully suggested to change the numbers as they feel like to fit the result they want. This, of course, isn’t a unique problem here – Lancer does the same thing, as do many other tactical games. I’d go as far as to say that the current standard for games like this is to make encounter budgeting only a guideline and mapmaking even less than that. We’re still relatively new to mechanizing fight objectives as a consistent thing. I’ve talked about this on the blog before. It isn’t really news.

But, where does that leave the ‘answers the GM is expected to accept’? In the fight rules only? Pretty much, even the skill rolls are GM call on stat, validity of a given skill, and the meaning of a success or a consequence. The power of interpretation means there’s almost nowhere to go in Draw Steel where the GM isn’t calling the shots. It’s just the fights.

An acquaintance posited a hierarchy of authority for RPGs a while ago, which I think is useful to keep in mind here:

- The social agreement to keep playing

- The GM

- The rules of the game

- The players

Essentially, something below on the ladder can’t do anything to violate the demands of those above it. The agreement to sit down and play the game was more relevant to the conversation as it came up – essentially, if the GM ever does something that prompts people to no longer be cool with playing, or that would tangibly prevent further play being possible without this being an accepted-upon endpoint, they face retaliation. In any other case, however, they’re generally afforded to do whatever they want. In particular, they’re above the rules, but the other players aren’t.

This is why a GM changing dice rolls is “fudging” and a complex conversation, but another player changing dice rolls is “cheating” and there’s nothing controversial about condemning it.

In essence, it’s a pervasive principle. As long as it’s true, there’s nothing any rulebook could do to counteract it, right? If the rules say the GM can’t do this, the GM does it anyway and the cultural expectations are on their side. You can say that’s improper play, and disclaim it. As a game designer, I’m happy to leave it at that. But, unless you’re entrenched in your ways to the point that the GM deciding to cheat prompts an active protest to the point that it violates the top of the hierarchy, that’s not really going to mean much in play.

The thing I’m curious about, then – why was this a surprise to me? Why was it a letdown to have the GM calling every shot in this subsystem, when I can ignore how it muddles the combat mode much the same?

I’ve come to three conclusions – two specific, one general. I think they’re all compounding factors that led to this reaction in my thinking. And I think they can shine a light on how people, or at least people who think like me, will look at subsystems and form expectations of them. (And, perhaps, how to design a subsystem that communicates itself better.)

Firstly, and most personally galling – it just does not work when left alone. The numbers do not function with the amount of rests you will get through. The GM needs to interfere and give other rewards, to specifically make room for a massive number of bonus rests at the end of each level, something. If the project numbers were tuned to the amount of rests a campaign would get without the GM handing out any bennies, this post would not exist. This is in part one of the cultural things from its D&D legacy – handing out bennies is strongly taken as given for this subsystem. It’s assumed the GM will be handing out more than the system produces as a default, and here and there it comments a vague suggested rate, if the GM happens to read that section closely enough. In essence, the GM’s job is to fix the numbers, and if they don’t, they remain broken. Rather than them tuning to be faster or slower from a baseline, they need to tune up to make it work at all.

I don’t know that there’s a lesson to be learned from this point. To be frank, this is the sort of thing I haven’t encountered before in any other game I have some respect for, and I’m just gobsmacked by it. I think the actual core of it is that the system wants the 10-20 downtime rolls per level to be the actual numerical baseline, but still wants them aesthetically tied to the rests you take during an adventure. Because those are very different rates, it then has to propose that you throw in a big pile at the very end to catch up, and hopes that will be intuitive enough for people. I do think sabotaging the pace of crafting was better than sabotaging the pace of combat rests, since the attrition is a lot more important there, but, still.

Secondly, there’s the core of how the crafting options are positioned in the system at all. The culture of D&D hands out loot relatively arbitrarily. It simultaneously ties it into numerical progression, provides average rates for how many magic items a player should have at any given time, and claims they’re an optional luxury that can be done without for a full game. Draw Steel makes much the same claim, and tells the GM it is not obligatory to give a player any magic items at all. (Let alone consider what magic items that player might specifically be keeping an eye on as worth giving, vs any other option on the list.) Crafting, then, is an option that seems to be available no matter what. Since magic items do mean increased damage output and health, they’re a boost that I would certainly classify as obligatory, given the choice between getting one and not. And, the GM controls when they hand it out, so the system seems to be presenting a choice you don’t otherwise have – when, in actuality, it’s still the GM’s choice, not yours.

The lesson I conclude from this is that the inclusion of the subsystem signaled and implied functionality that wasn’t there. Which brings me to the third conclusion, the general one: including a system signals to readers that it’s an option, one they can engage with as they would wish to. Including a mechanically detailed system is a much more significant signal on this front. And, projects do distinctly appear to be that! You have several progress bars to juggle as you pursue different things, a laundry list of goals to want, numbers to crunch to figure out what your roll bonus will be and if you need to invest further before heading onwards. Because there’s so many mechanical hooks to look at, as a player, I see something to conceptually orient myself around. That’s what mechanical detail expresses, on an aesthetic level, before you even get to the gameplay.

That’s one of the reasons why combat systems are the way they are. Or rather, there’s a feedback loop to it. Combat is conceptually difficult and complicated – if you want to model it, structured and detailed mechanics are very important. If you include those mechanics, players are drawn to them and centralize gameplay around it, in comparison to lighter subsystems. The mechanics themselves signal this with their presence, and, implicitly, their rigidity offers a reprieve from the GM calling all the shots. Within the domain of the mechanics, the ladder can flip, and now the GM is subordained to the rules, too. The players never get to be on top, but a temporary changing of the guard is still a very exciting prospect.

As designers, that’s something we can take advantage of! Something I had, honestly, taken largely for granted until I sat down to examine this impulse. Where there are rules, I will go, because I enjoy interacting with rules. That makes sense to me. But that’s not the only reason. Where there are rules, I can know the expectation is that this is going to happen. Where there are lots of rules, detailed rules, I can know the expectation is that this will be in focus, will be relevant to the point that all this detail was called for. In a system with as many combat rules as D&D, I know I have to be ready for a fight. That extends to Draw Steel. And within that fight, the rules are calling the shots.

If you present a mechanically detailed subsystem, this is how I’ll implicitly interpret it. When that’s a signal you want to send, there is aesthetic value in detailing those mechanics. It will communicate to your readers.

Draw Steel, ultimately, wants the GM to be in full control in the game and able to do whatever they want. It’s an inheritor of D&D, that’s really to be expected. The whole OSR movement sprang up out of a desire to preserve GM sovereignty over the encroachment of rules (that’s a somewhat reductive framing, but I’ll stand by it). The reason that it interests me, as a player, is that its combat doesn’t do that in the way that, say, Daggerheart‘s does. Within the domain of a fight, the game is not serving the Game Master, but the other way around.

But, that’s only within a fight, it turns out. Even among the other modes that look that way. And I think that’s a bit of a waste.