…Ugh. I do not enjoy this.

So, a disclaimer. I am a rather negative person, in demeanor in general, but especially in critique. I try to make a point of reining that in when in public. On this blog, and on other public platforms I show up on, I have a policy to focus on talking about things that I think are good and worth getting eyes on. By default… I’m meaner about a lot of things, and that means I have to do a bit of ‘putting on a face’, even for this blog. (Sorry, folks, you’re not getting my entirely authentic self. To anyone parasocial and devastated, my not-quite-sincerest condolences.) This post is born from that, so if I seem crueler than usual, my apologies.

I have a long list of things, games, systems, people, that I don’t like very much. And those do tend to color the way I view other, related things. If I dislike a system enough, and I see a different game is built on that system, sometimes I just give up on that game without looking at it further. Sometimes, if I find an author’s work consistently bad, I’ll inherently mistrust the next thing they write. Is this unfair? Yeah, a bit! It’s a personal privilege due to there being a lot of games I can enjoy out there, so, I’m happier indulging my pettiness than I am trying it all no matter what.

Thus, I do feel obliged to mention. I, the author, have some amount of an axe to grind against Caltrop Core, a prior system by Titanomachy RPG, the author of, well, I’ll get to it. On some level, this colors my reaction. It predisposes me to disliking what I see, and, I’d feel manipulative for not acknowledging that. (I’d also feel rather needless enumerating my dislike of that system here, if there’s a lot of interest I can bring it up later, but, for now this post is already bitter enough, and I don’t want that to grow any more than it has to.)

That said, this is also the product of discussing this piece with several other acquaintances, whose reaction was similarly unpleasant, and who do not share that arbitrary bitter predisposition. Some of them are generally quite positive and lovely, in fact, and seeing the ways this upset them is really what prompted me to write this out.

This is Possibility Crisis, a… well, it’s not a game, but it’s a project for public contribution, a world to make games in. By, as I said, Titanomachy RPG. The concept is that people will take the origin point of this world, elaborate it by creating pieces of it, and thus, a community around the games and world will grow in the process of creating it. It’s a clever structure, even if these sorts of innate community-building endeavors don’t tend to appeal to me. If the seed was something that inspired me, honestly, I think I would appreciate something like it.

The actual content of this world-seed is…

Baffling, is probably the most generous way I can put it.

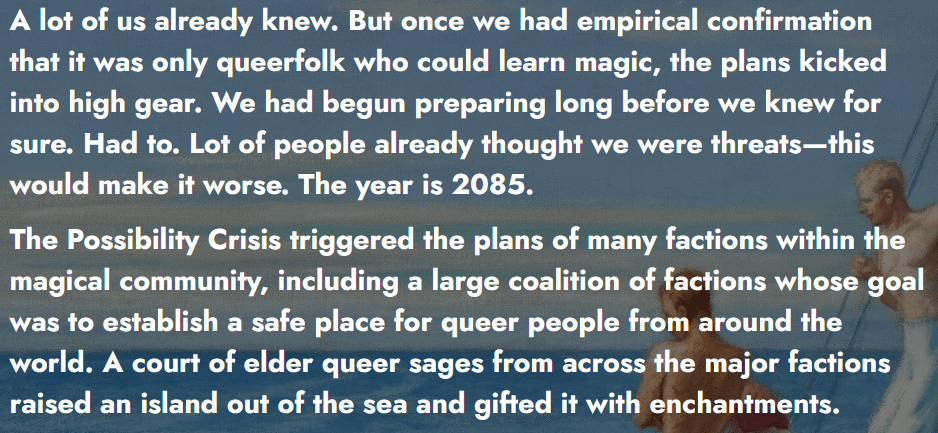

This is the general pitch on the itch page. It’s several decades in the future, magic exists, and only queer people are capable of it. Hence, several groups of magical queer wizards have banded together to construct a magical island as a safe haven, which travels the world.

The vision of the world beyond is… dubious. To those uninterested in the continental United States, it is an entirely blank slate, and within that context, we have painted a vague vision of calamity, with a strong current of Those Evil Southerners. For those without the extremely specific context of the intensely-tiresome US geopolitical landscape: the southern states trend more right-wing in their elected political bents, for a variety of reasons. This is, of course, bad for the people living there, especially the queer people. It also sometimes prompts a particularly awful sort of callousness from people inclined to tar entire states full of people with that brush, in the vein of, “oh, people in Texas deserve what happens to them for electing Republicans over and over.” As someone with queer acquaintances in Texas and Florida, this is horrendously cruel, and the common second comment in that vein, “perhaps they should move,” is also cruel, but more insidiously so. To lose one’s home, especially to have to travel far away to somewhere new, is no light thing, and claiming that it is the fault of those driven out is a horrendous failure of allyship and support. If you hear anyone say anything to that effect, that means they do not respect your value as a person based entirely on where you happen to live, and they are not your ally.

Now, Titanomachy has not said any of those things. And I don’t wish to claim that’s their intent in this paragraph. But it’s certainly the veneer, alongside a sort of sneering “our enemies are incompetent” vein. That is, Texan militias (all right-wing and evil) are inherently defeated by the “superior Mexican military,” a phrase that strikes me as very out of place in a text that would otherwise seem to benefit greatly from not fetishizing militarization, and Florida’s consumption by Disney is a running gag among people inclined to mock the Republicans there.

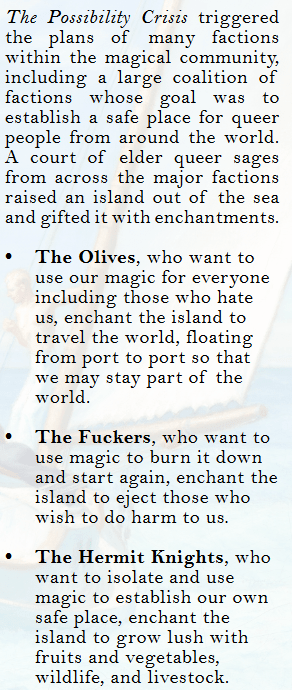

The island has some more elaboration to it, but, this is where things really start to get alarming. Mentioned in equal measure are a group of violent accelerationists and complete isolationists, and only then in the final faction do we get any notion of these being groups that are not considered fine and dandy in this hypothetical utopia. (The tone whiplash of half of them being called “Shiteaters” or “Fuckers” and half of them having names that I would recognize as, faction names in a story of magic and politics, is its own complaint, but much lesser than the structural concerns at hand here.) It presents the island as “a fresh start for anyone who wants one,” prompting one to question if we are to assume the Olives are somehow a ruling faction or considered the “right” one, since, that certainly doesn’t seem to suit any of the other concepts offered before us, but, an outwardly hostile veneer and isolationist perspective seem to be supported later on as the ideal, so, no?

It’s trying to be a queer power fantasy. And it is also trying to engage with politics, which queer life in the modern day cannot help but do. But these two goals are not easily compatible. A power fantasy is a complex thing to examine, from a political lens, and not one to easily indulge in. The concept being presented is a semi-isolationist state where queer people have inherent power due to the nature of magic, and inherent structural power due to magic being a core part of how the island sustains itself. This is presented as a triumph, as a utopia, because we assume the reader is queer. And thus, the reader will hear “this is a group of people who can exclude and hurt your enemies, and you can have power over them,” and they will enjoy that. However, I cannot have that and also be genuinely invested in or thinking about the politics at play. If I want to indulge in a power fantasy like that, a prerequisite step is forgetting what a power fantasy like that means, and what ideologies would sell it to me. I don’t want to think about suffering under the boots of power, and then be told, “now you can have power!” and have the followup left unstated but very much gestured at. Especially with what queer separatism has tried to do to people like me.

Which brings me to a more personal reason to feel alienated by this.

This one, I am willing to presume is not the intent. But it was also the first thing that, when reading, made me sigh and go, “ah, got it, this is not for me.”

As an aro/ace person, my relationship to queerness is, complicated. And that is immediately a fraught statement. There’s an unpleasant history of people attempting to externally litigate whether I, or someone like me, can count as [truly queer]. And, my immediate stance, and if you disagree, shut up, is that, yes, I do, and anyone like me does as well.

But, that’s easy to say, and more difficult to internalize. When I realized I was trans, a part of my initial rush of relief was realizing, now, I would likely never be denied being [truly queer] again. That’s an experience I’ve known several other trans people to share, in fact, which speaks to a certain exclusionary vein in many queer spaces I’ve frequented. If you aren’t considered legitimate enough, you will have an inherent push of discomfort at you for your presence in the space, and, often, that gets internally amplified. Which is a reason I’m discontent with the premise in general – being able to draw an easy line between [truly queer] and not based on, hey, you can do magic, simply will never sit right with me.

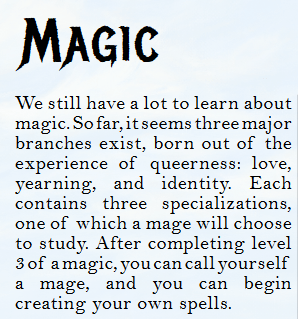

Here, however, it tells something more than that. It tells me that [love] and [yearning] are fundamental queer experiences. That to be queer, as this game-prompt describes it, those are parts of who I am.

I have, in my own scattered notes, a concept of a game exploring queerness. It’s something I come back to every now and again, but it always leaves a bitter taste in my mouth. I don’t know if I’ll ever actually make and publish it. The premise is as follows:

Magic is real, and powered by [true love]. You are among a group of chosen ones, who must use this magic to fight against a great evil. You are aro/ace.

Now, it is popular recently to expand [love] into more than just, attraction. Love for one’s hobbies, or love for one’s friends. But, I find that rather dissatisfying. There are words for those sorts of relationships, too. And it removes the exploration of the ways people actually do relate to attraction of various kinds, how that intertwines with their other forms of interactions, and what that is like for someone who Does Not Get It, especially when pressured into going along with it nonetheless. If [true love] gives power, and power can save the world, do you have a right to express discomfort at [true love]?

Like I said, it’s a bitter idea. It’s dear to my heart, but hard to work with for long.

Things like this remind me of it. Things that say, “ah, being in love, yearning, these things are fundamental experiences.” And, for a lot of queer people, I’m sure they are! I don’t mean to discount that at all. But I don’t feel that way. Even in broader, abstracted forms of these definitions, the times I would yearn for, say, a more-fitting body are rare. The times where I care for those I know intensely enough that it might be called “love” are also rare. Matching those titles to my experiences would, at that point, be stretching them to accommodate who I am. And if that, why not stretch them to accommodate anyone? If I love, surely straight people do. This providing of the magical bounds of queerness tells me, I am not queer.

No, worse than that. It tells me, if I found myself in this world, and the world deemed me queer, the powers I got would not suit me. I would feel invalidated for my empowerment. And, of course, I would feel invalidated lacking it! That would be the world cosmically saying, I do not count as queer. And, how dare you, world! You do not define me.

Now, these are critiques of the concept. And, like I said myself, I find the concept of magic entwined with love, or identity, or queerness, or whatever else, fascinating at times. I don’t want to say, this concept should never be explored, or this concept should only be explored in a way that satisfies my fringe existence in particular. If this expresses what queerness is to the author, fair enough. But it rings hollow, it rings exclusive, to the ear I have trained in my heart.

It’s not queerness as queerness is to me.

And now, the part that convinced me to write this post.

Some of these are fine. Mostly the ones exploring the island itself and the relevant locales therein. It’s the first and fifth one, the red ones, that leapt out to me immediately. It’s these that set off my alarm bells.

The last one, the JK Rowling pastiche, is just, entirely hateful. The whole of the prompt is, “You know this person you consider an enemy? You can ruin her life now.” There is no other way to read “she just laid off the majority of her security” and the mention of her not being at home as anything other than an invitation to intrude on the place and… well, it’s left unclear what, exactly, presumably whatever the players feel like, noting that they have literal magic on their side. It’s the entire power fantasy of the pitch laid bare, and exactly what I was disquieted by earlier. “Imagine you could hurt these real life people.” I can’t say I don’t understand the appeal, and I wouldn’t particularly bat an eye at someone having a fantasy of hurting someone who has done a lot of harm to the world, but you cannot sell me a power fantasy and a utopia in the same package. If I am to be working to foster a community and make a better world for all, or, at least, for those the queer separatist factions and the metaphysics deem worthy, then, do not also tell me “hey, here’s an opportunity to cause problems for this celebrity cameo you hate, give it up for being mean to JK Rowling, folks.” And in trying to be both at once, with a mean-spirited veneer, it simply makes me, disquiet with the utopia. It reads like a story being told in a fundamentally unpleasant society.

If I were to write anything for this setting, and, in truth, I did ponder it, it would be of those marginalized by the expectations of the writing. Of those that would not be considered fitting for the island, or the magic, and how they navigate a world where their ostensible allies are seemingly interested only in themselves and those they seek to hurt.

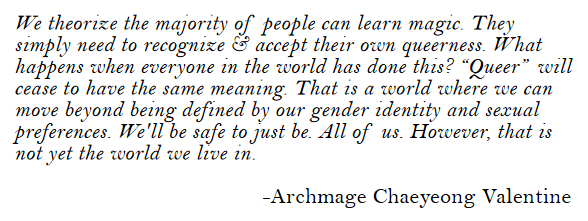

As for the first prompt, I wanted to bring this quote up. It was put at the beginning of the booklet, but I noticed it last. And, in truth, it frustrates me. Not least of which for the angle of, “oh so many people are secretly queer and haven’t even realized it,” but in context of the first prompt? Of the Bad Gay Man? In the same breath, it says both that magic is from self-understanding and if everyone could embrace who they truly are then it might not be locked to queer people at all, and that a politically powerful bastard who happens to be gay can be a problem in a way that he never could if he happened to be straight instead. He has power because he is gay. Not because of any deep inner recognition of himself. I have had many deep conversations with cis people coming to terms with their gender identity, with straight people coming to terms with their attraction. Many lovely internal explorations of who they are. That introspection holds no weight here. It has nothing to do with power. You can be selfish, and cruel, and awful, and so long as you happen to not be a very particular subset of arrangements of gender and sexuality, there you have it.

The prompt seems to take as given that queer people are good, and should be protected, and their vision of a bad queer person is one who hurts other queer people. To that end, being exclusionary, being cruel, being violent – these are fine, as long as you’re in support of the group of [truly queers]. There’s an us, and there’s a them, and we will empower the us and keep the them out.

Like I said, that’s a nice fantasy, but taking that bent to real modern politics that hurts a lot of real people is miserable.

And, I mean that literally. I showed this thing to a group of friends when I stumbled upon it, and, universally, people were hurt. It upset them, it invalidated them, mostly it just activated all of their “oh I recognize that shitty ideology” alarm bells and I can absolutely see why. And that frustrates me. To see something talking about queer existence, something trying a novel structure in the space of game design to build a design community, and the result is it hurts people to read…

I hate that.

And, I don’t know what to do with that. In all likelihood, this post won’t do any material good, right? The best I can hope for is someone reads this and learns a bit on other perspectives of queerness and structures that support that, but, that’s unlikely. Mostly, this is just me spitting vitriol into the void, and either nothing happens or it spits back. I’m wasting my time either way.

But, I had to write these thoughts out, and I had to at least know that they’re out there. For someone to read. I don’t want Possibility Crisis to exist in the world and have people look at it and all they see is people nodding along and collaborating with that. I don’t want to be part of a community that does that.

Honestly, at times when writing this, I thought, “maybe the queer community isn’t a place for me.” And I don’t want a document that does that to exist uncommented on.

So… here I am making an angry callout post, I suppose.

I don’t have a better conclusion than that.