Roleplaying is a creative exercise.

I forget this, sometimes. Pretty continuously, as a matter of fact. I play a lot of roleplaying games on a regular basis in my life, and I also do creative work outside of them. Every so often, I find myself frustrated at a lack of creative energy, and I try to figure out where it all went. Keeping in mind how much writing I’ve done in the games I’m playing gives context to that, context it’s easy for me to forget about.

It’s group storytelling, and that’s a fair bit of work. Everyone’s writing.

So, if you’re reading this and you’re a player, or especially a GM, give yourself a pat on the back and a bit of a break every so often. Whatever spot you’re in, you’ve been doing more creative work than you might realize. That’s something to be proud of! Honestly, you can probably count it as creative writing practice, if you feel the need to categorize activities as productive or they nag at you.

However, it’s not quite the same thing. Writing is an exercise in omnipotence, among other things. You sit down in front of a page, and it can be anything you set your mind to. You can make people up, and you can kill ’em off. You can invent new concepts out of nothing. There’s a lot of things you can write about, and nobody can really stop you. Which, heck. If that sounds fun, and the prior paragraphs are resonant? Consider this a call to action! Stop reading someone yell about a niche art medium and their hot takes on it, and go write something that satisfies you. Live your best life, and make what you want to make. It’s important. Writing is a lovely experience, and there’s essentially nothing in your way but the energy cost of getting started and keeping going.

That’s not true of RPGs. Those have a lot in your way. If you sit down to play an RPG, and just start declaring whatever you want, in the way that a writer would, you’re gonna make your friends mad at you. None of them came here to watch you be omnipotent while they sit around. If you want to arbitrarily make someone up and then kill them off, you’re going to get protests along the way. Probably, someone pulling out a rulebook to cite at you, saying why you can’t do that.

Writing doesn’t really have a “you can’t do that”. It has “you shouldn’t do that,” which is a different kind of thing. RPGs, however, are made of both.

When writing, you make something true by writing it. Or, semi-true. You can write lies. You can write through perspectives that lie about what they see! But writing something places it into the world, into the understanding of the readers. And that’s a simple action.

When playing an RPG, how do you do the same thing?

Well, probably, you write it. Or, speak it. (We’re having [writing] include [storytelling] here, so the distinction isn’t too relevant right this minute.) And then you look around the room for approval, and get a yes or no depending on how the other players react.

How the other players react is determined by the rules of the game, the roles you occupy, and the expectations of how it works. Or, in other words – “am I allowed to write this?” is the fundamental question that rules design is made to answer.

Mother, may I?

When playing a GMed RPG (which this post will mostly focus on, though I think it’s applicable to other dynamics), there’s an elephant in the room. The GM. When you turn to the room and silently ask for approval for the latest thing you wrote into the world, usually, they’re the ones who get to actually say yes or no. The other players don’t really have a vote in the same way.

They do have a vote in a way. If they ooh and ahh and go “yeah, that would be cool,” or something to that effect, that means something, right? But if all that happens, and the GM says no despite that, then their vote didn’t really matter.

A GM narrates a world. Narrating is, as we’ve defined it, writing. They say something, and lo, it is the case. There’s a chandelier in this room. The sun is setting. The captain’s impassive stare flickers, ever so briefly, with a smile. They can do this about almost anything, and have it be accepted. In fact, they kind of have to – if they don’t, none of the other players will have an idea of what’s going on, or have much of anything to do, beyond of their own initiative. Being a writer is one of the jobs of being a GM. A full writer. They have the omnipotence.

Suppose you’re a player, and a GM writes at you. “Your character opens the door, spots an old man, draws their sword and stabs him.”

What’s your first response to that?

Some variation of “What? No I don’t!”, right?

Now, that’s kind of an extreme example, and in less extreme versions, it can get blurry. But it makes the point well. The GM can write the world just fine, but if they say what a PC does, that’s overstepping a boundary, in a way that it naturally can’t be when a writer says what a character does in their story. The GM’s domain isn’t supreme, it’s just almost that.

In fact, let’s formalize that concept, it’ll be useful. An authorial [domain of authority] is a space where a given player has the power to write, as we’ve defined writing here. The baseline dynamic set up here gives the GM a [domain of authority] covering all the world, except for the actions of a select set of entities, the PCs. Each PC has one player, whose [domain of authority] covers the actions of that one PC, and nothing else. Nobody has quite the same level of power as an author of a book does, but the GM gets pretty close, and the players get pretty close to nothing.

Since social dynamics trend towards wanting to feel “fair,” for as nebulous a concept as that may be, it usually blurs a bit more than that.

Suppose you’re a player in this scenario. You have a thing you want to see happen. It’d be exciting, and cool, and satisfying, and, you know, whatever other positive emotions you feel like. How do you get that?

There’s a lot of answers, but, the simplest method, really – you ignore whatever rules govern what’s going on, you turn to the GM, and you go, “hey, wouldn’t it be cool if this happened?”

I’ve done that. A lot of people have done it, in my experience. It’s a pretty natural impulse, especially if you’re less cognizant of the power dynamics in authorship being explored here. There’s a person whose job it is to narrate things, you have a cool idea for them to narrate, go for it!

That’s a pretty straightforward expression of authorial power. The player had a vision of something they wanted to have happen or exist, and their actions made it be written into the world. It’s certainly extending beyond the limits of their [domain]. And it’s an entirely natural part of the dynamic!

But!

All of that is only true if the GM approves. If they go, “sure, that would be cool,” and exercise their authorial power to make it happen. The players haven’t actually gained adjudicating power, it’s more like, they’ve gotten a position as an advisor to the king. They can sway how things go using social pressure, but they don’t actually have a tangible authority to back it up.

Now, that isn’t to say that social pressure isn’t nothing. In fact, it’s quite a bit. In material terms, the authorial power of players can be augmented by stunts, and everything I wrote about how those work is just as applicable to expanding authorial power. A GM who gets a lot of “hey, wouldn’t it be cool if” pitches from their players can build up [no fatigue] and [yes fatigue] all the same, and the players will be able to get some, but not all, of what they’d like to author. In a game where it’s much more sparing, depending on the GM’s demeanor and the specific social dynamics at play, the players might get to be de facto second narrators, just because the GM is willing to rubberstamp whatever they propose.

Actually, it’s a bit worse than with stunts. Or, more intense, to avoid making it a judgement. The ambient social pressures of GMing as a concept are directed towards making the authorial balance more “fair,” and even if players don’t consciously propose anything, the GM is still on the watch for what might be implicit proposals. Among the expectations put on a GM are, they have to make the player’s actions meaningful in affecting the world, and they have to go where the players are interested in going. If the players express an interest in a facet of the world, the GM has to have enough there for their interest to be made worth it – and, whether that’s improvised whole-cloth or it’s part of an extensive prep suite that covers every piece of the world in interesting details, the details that get to be actually narrated are the ones that the players focus on, and that informs what future prep would be the most valuable. Player interest is the passive pressure that pushes the GM towards certain objects in their narration. Nobody wants to be the GM going on at length about elements the players are entirely tuned out for.

And if that’s the passive pressure, player actions are where it gets stronger and more, well, active. When the players take an action, and they mean something by it, and it doesn’t change anything, that highlights the power dynamic at play. If what the PCs do doesn’t matter, and the only thing the players can write is what the PCs do, then the GM really is a writer in full, and the players are just along for the ride. Now, I don’t actually hate experiences like that. I think they can be quite fun, if everyone involved knows that’s what they’re getting into. But, if not, then the impulse is to make things “fair.” And that highlights just how unfair this all is. You’d risk player disgruntlement, disinterest in what happens if they can’t meaningfully engage with it, and worse. Plus, following along the prior paragraph, one of the most consistent signals that a player is interested in something is that they have their character interact with it. The GM implicitly reads player actions as signals, as a result, and has to ensure the directions pointed at are both elaborated and dynamic enough that the players will be satisfied by what they find, and compelled by the changes they can make. When the GM presents challenges to the players, or decision points to shape the outcomes, they make this explicit – they write multiple things that may be the case, and then the players gain the power of selecting which one. That selection is both an expression of authorial power on the players’ end, or, pseudo-authorial, and a signal of interest to inform the GM in future. By getting into a good rhythm, the GM can loan out quite a bit of their authorial power here.

But, the inverse to all that is that if the GM doesn’t feel particularly swayed by these social pressures, they absolutely can just run it with the power dynamic as-is, and there’s not much the players can do about it. All expanded playerside authorial power comes at a loan, and the GM has the final say in where it goes and what it means. The players haven’t expanded their domain, they’ve been graciously invited onto someone else’s lands, revocable at any time. We request that they be a merciful king, but, as with everything else – it’s nothing more than a request.

Border skirmishes

Let’s talk about social interaction.

No, everything I just wrote didn’t count. I mean in-game social interaction. Character to character. Persuasion, more specifically – which is much more common in RPGs than it is in real life, proportional to other types of interactions. Trying to get someone to do what you want.

Let’s invent a strawman game mechanic. By which I mean, let’s use a version of D&D 5e‘s mechanics – not the version in the rules themselves, but the version I commonly see implemented by people who don’t want to bother with or don’t know about the slightly more nuanced attitude system in the Dungeon Master’s Guide. Roll 1d20, and add a couple numbers representing your bonus with Persuasion. If the total is higher than 15 (or some other arbitrarily-assigned number), the target does what you want. Easy-peasy.

This flanderized version of the mechanic, and, honestly, even the full version in the DMG, tends to ruffle some feathers. And you might have a gut feeling as to why, but, dear reader, I’d like to request you ignore that impulse, and try to think of it logically. Why is it that this prompts protests, and (in some spaces) calls to eradicate social skills from skill lists entirely? Why is [this person is the obstacle to us continuing, let us roll to bypass it] a problem, but [this cliff is an obstacle to us continuing, let us roll to bypass it] kosher? On a structural level, there isn’t actually much difference between the two. The presence of Persuasion as a skill is actively because people will appear as practical obstacles that the PCs must find a way to deal with, after all. What’s so different between “the guard lets you pass into the forbidden lands” and “you swim across the lake into the forbidden lands” as results of gameplay?

Or, if you’re the overly clever type to try to outthink any puzzle sent your way (in which case, so am I, I tip my tiny hat to thee) – why am I asking this question, and why in this blog post of all places?

The trick is, this is an intrusion. It’s the players stepping on the GM’s [domain]. Now, in a way, all of these examples are intrusions. If a player wrote “the door unlocks when I try to open it,” or “I climb up the cliff without issue,” the GM would be well within their rights to waggle their finger and demand a roll, or forbid outright. But, the output of such a roll could then, itself, write “the door unlocks,” and the GM would accept that, even though it is indeed writing under the GM’s domain. But. If the system wrote “the guard decides these people are trustworthy and lets them pass,” that’s not just writing into the GM’s domain – it’s specifically writing into character psychology.

Characters are complicated things, in an RPG. They kind of have to be, for players to have anything to play with (after all, their domains are so much smaller). The GM’s characters are necessarily less complicated, to avoid completely overwhelming them, but they are still afforded complex dimensions to write about – motives, fears, desires, backstories, whatever. You know, characterization beats. A social roll letting the players write over things like this is more of an affront than if it allows them to write over other parts of the world, because characters are more sacrosanct. You commonly see complaints that diplomacy skills function like mind control, but not explanations for why mind control is less agreeable than the body control of forcing a locked door open. It’s taken as a given, when you get down to it – characters are a more deep and true aspect of one’s domain, and so it is a greater act of war to be pierced to that point. Players don’t get to write into characters they don’t control, and the system seemingly allowing them to do that is seen as a violation.

This does go both ways. In fact, it goes stronger the other way, in my experience. The character is all a player has, remember. So the GM writing into what a given PC does, or feels, is something I often see balked at in the strongest possible terms. I see a lot of GMing advice frame this as one of the greatest crimes one can commit – narrate everything about the world, but never touch a character’s interiority. You can present them hazards, challenge them and try to frighten them, and, perhaps, you should! But simply writing, “you are afraid,” that gets criticized, quite a bit.

Now, I don’t really agree with that. Honestly, I’m a big fan of cerebral narration in my RPGs, what people are thinking and feeling, and when I GM, I’m happy to present players with things their characters face, and include “here’s something you feel about it.” You can nudge characterization in interesting ways, if they’re feeling a bout of nostalgia and we haven’t seen them like that before. I honestly solidly recommend it! If you have a group that’s comfortable with it. But, if you don’t have players comfortable with that, this is why – their character is the limited domain they have authority over, and psychological interiority is presented to be one of the most sacrosanct parts of someone’s domain. Narration like that is an invasion, if they aren’t on board with it.

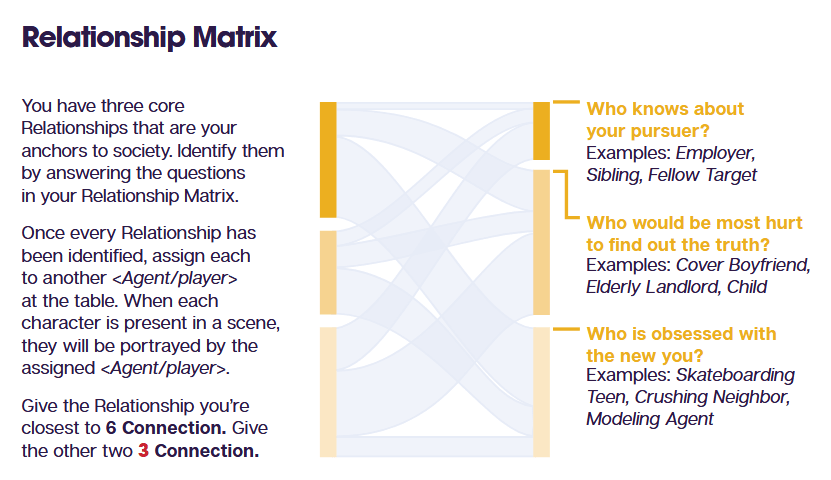

There’s ways to set things up without being an intrusion. Triangle Agency, for instance, which also has a lot more fascinating tech and this is honestly one of the less interesting parts of it so please check it out, has these, as part of character creation:

It’s a set of three relevant NPCs to whatever your mundane life is like. (In this case, your mundane life is a cover identity on the run from a checkered past. “Mundane” is relative, okay?) And control over them is explicitly handed over to the other players, rather than the GM. Those players then control those NPCs whenever they show up, which they’re supposed to do semi-consistently, and the GM has no say over it.

That’s an intrusion, right?

Well, no, is the thing!

The game itself has set this up as a convention. It’s something everyone playing is cognizant of, and has formed their understanding of the domains around being the case. Each player’s domain to write in is their own PC, and the actions they take… plus, the companion NPCs to the other players that get handed to them to control, and the actions they take. The GM’s domain is the entire world, except for the PCs and their actions… and, except for all of these recurring companion NPCs, and their actions. When a companion NPC shows up and a player starts controlling them, the GM won’t internally get upset and then remember that this isn’t their department – it’s already been established, and so, it’s not an intrusion.

Advance warning

There’s a particular sort of RPG horror story, one which I encounter much less of nowadays but do still spot here and there.

The short of it is, in essence – I’ve got a cool campaign set up to go explode the evil Renraku skyscraper or what have you, but the players have all made characters that actively don’t want to do that and are refusing to play what I’ve set out for them. They all want to run around ignoring the premise of the campaign as I pitched it. What do I do?

Now, the reason I don’t encounter this sort of thing as often nowadays – I hope, it’s quite possible the actual reason is I’ve just moved to healthier RPG spaces and I don’t see the bad stuff – is it’s now generally understood wisdom that you do in fact need to build a character to fit the premise of a campaign. If the game is being pitched as about hunting a dragon, don’t play someone who refuses to hurt dragons – or, at minimum, make it so they’ll make an exception for this one.

In other words – this is another constraint on the authorial power of a player. When they write a character, they have to write a character that fits into the story they’re in. If they don’t… the character doesn’t fit, and they can’t really play the game and continue the story, right? At best, you get the party puttering about doing something else while all the GM’s prep and interest is wasted. That’s not a healthy result, so, this becomes a solid restriction in writing.

Now, interestingly, this is a restriction on something I haven’t talked about up until now. It’s a restriction on character action, too, in that players are not supposed to narrate actions that will fundamentally take them out of the path of the game, but usually that’s a broader space it can cover. In the initial setup, when a player is writing their character into existence, that’s what’s being constrained. Their options go from everyone to “everyone except Jane Doesn’t-Like-Hunting-Dragons.” The end result of their backstory, whatever else it yields, has to be someone who will go play the game as it has been pitched to them. A constraint on the backstory step, as well as the backstory step itself, is new.

There’s another particular sort of RPG horror story, which has also fallen out of fashion. The person who shows up to a game with a veritable tome of backstory, establishing powers, world elements, and whatever else their heart desires. Someone using the backstory as a vector to establish a whole bunch of nonsense about their character and the world, because, they can write anything, now can’t they?

In other words – creating a character, and the context around that character, is an authorial affordance to the players. A much bigger one than they’d get anywhere else.

When in the midst of play, narrating a whole location as a player is a significant faux pas. (Unless the game is actively set up that way, or your GM is happy to rubberstamp almost anything – and even in those cases, it’s significant.) Narrating dangers, even moreso. Just suppose Jane Doesn’t-Like-Hunting-Dragons were to announce “suddenly vampires attack” in the middle of the GM trying to set up their complex political dragon-intrigue (I may have lost the plot a bit, but that’s fine, so did the GM). That’s not fair! Jane can’t do that! She’s stepped way beyond her domain as a player. Writing things like that is solidly the GM’s job.

But, suppose Jane came to the table with her character pitch, and in her backstory, wrote about the secret volcano-island where she was raised in secret by a group of humans hiding out from the vampires that ruled the land. Taught strength and honor and to not hunt dragons, or whatever else.

Well, that’s just cool, right? It’s an interesting tidbit of worldbuilding, and gives some context for Jane’s cultural background as a character. It gives the GM something to fit into the larger world, too. It might be a bit out-of-genre, and then you need to discuss that – but what it isn’t is an overreach. Jane totally had the right to write all that, even though she never could’ve gotten past sentence two if this was in play.

In the setup phase, then, the domains are different. Each player has the right to establish parts of the world, including locations, groups, and significant enemies to be faced in the future. They don’t control these elements past this point, but they can create them, and inject them into the wider domain of [the world and the plot of the campaign], which the GM still controls.

The GM once again maintains veto power, these are injections into their domain, but they’re expected to take a much lighter touch. “That’s cool, let’s see if we can make it work” when something doesn’t fit, rather than the fundamental affordance given to the GM and not the other players – “no”.

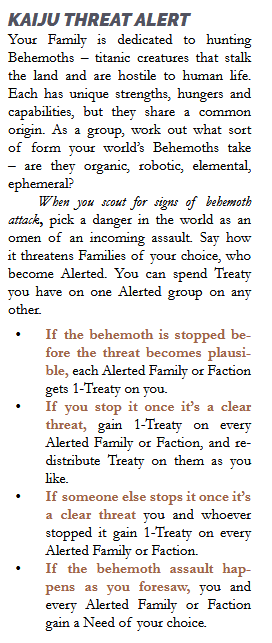

For some games, this isn’t just an implicit step. In Legacy: Life Among The Ruins, and actually even dating to the original Apocalypse World, the build choices you make when creating a character explicitly include elements they add to the world, and you’re allowed to customize the details. In a sense, this is more constrained than just getting to write anything you want into the world, but it’s also definite. The GM isn’t allowed to veto the existence of giant rampaging monsters, when you take the playbook with this move:

In fact, a lot of the options you take in character creation fill in these details in an authorial manner. Depending on the stat spread and build options you pick, you establish a history with the other players’ factions, landmarks to exist on the nearby worldmap and explore/be threatened by, and more:

These are, again, authorial powers granted by the system in a more specific way, but each player option gets these, tailored to the concept they represent. When I played Legacy, I got to play the zombie apocalypse faction from one of the expansions, and picking that option tinged the whole area and themes of the story with the genre of, [this is now in part a zombie apocalypse story]. I got to add a haunted asylum to the map. The specter of GM disapproval did still hang over all of this, but, in codifying these powers, it made it so that being a player during the setup phase of the game was, very directly, being a writer. This is the step where you can declare things to be true.

Fabula Ultima takes it one step further. The entire initial setup of the game, world, villains, and all, are done as a collective effort. Rather than backstory-elements being written within a broader context the GM establishes, essentially, everyone has room at a collaborative writing table to figure out what the world looks like, and what big bads you’re gonna be hunting down. In terms of individual authorial power, this is kind of a reduction, since collaboration is always a headache – nobody can just say something and make it so, they’re subject to vetos or reinterpretations from everyone. But, in terms of how the power is distributed to players vs the GM, the GM has no special privilege or dominion over the world – their ideas are just as vetoable as anyone else’s.

Except…

There’s an inherent followup step. Right? To all of this. A step where you transition from [setting up the game] to [playing the game], and the GM regains control over their domain. And that includes interpretive power. Everything the players get to write in at setup time become subject to GM focus at run-time. In all of the games mentioned, and beyond, whenever I write stuff into the world I’m excited with, it’s always tagged with one thought:

“I really like this, I hope it comes up.”

The setup phase gives players authorial power far greater than they’re usually allowed when in play. But, for that authorial power to actually be impactful, it has to come up in play. And that remains the domain of the GM. So, for as excited as I get about what I conceptualize, and as excited as I try to get everyone else about it? As a player, all I can really do is hope.

Mightier than the sword

Fabula Ultima has another ingredient to its authorial power dynamics. The players have access to a metacurrency (“Fabula Points”), which, alongside being useful to boost failed rolls, has:

(The GM indirectly has an analogous metacurrency, each major bad guy has a pool of “Ultima Points” that can also be spend to boost rolls, but they don’t have this authorial utility – instead, the GM’s implicit control over their domain lets them write things for free.)

The strongest use of this, in terms of how much it lets you write, is if you’re in an unspecified context. You can introduce a whole location to the map, and, as presented, unless that location is within a wider defined context, the GM doesn’t get to veto it. That’s pretty nice! But, in any context other than that one, the GM’s veto holds. You can spend a Fabula Point to propose an idea, in other words. (It can be thought of as a formalization of the fact that you can already do that, just in social terms, by speaking to the GM as a person.)

Even so, it is a pretty significant possibility for the players to intrude on the GM’s domain. Fabula presents itself as fairly radical in democratizing the authorial power here – it’s hardly the only game to have a mechanic like this, Wilderfeast and even Exalted 3e have options to add things to the world or local context (and both are similarly constrained by GM approval), but these things do indeed let the players be writers more than games where the GM just ignores all proposals and writes everything themself. And, while Fabula, Exalted, and Wilderfeast all could totally be run by a GM who just vetoes every proposal that reaches their desk, an argument could be made about that violating the [spirit of the game], or some other such intangible failure. Whether that argument actually sways the GM is hypotheticals on hypotheticals, but rhetorically, it’s a stronger leg to stand on, at the very least.

Curiously, however – remember what I said just a moment ago? Fabula Points’ usage as a limited capacity to write is a second utility. Alongside a primary power – juicing rolls to ensure success. Making sure you win, and win as hard as you can.

Instrumentalization beckons, in other words.

The value of a Fabula Point is penned to a gold standard. It can be about +3 to a roll, more if you rolled really badly, more abstractly, [a decent shot at converting a failure to a success]. From an instrumental perspective, an expenditure of a Fabula Point on world details wants to be at least as valuable as the benefit difference between a failed roll and a successful one. Now, the calculations for this are actually made a bit complicated, since “a villain appears and attacks immediately” would be a net gain thanks to some other elements of how villains work in the system, but, in broad terms, it’s about what you’d expect. A point expenditure to introduce a convenient bridge across the chasm the GM presented as a threat? Great! Effectively an autopass for multiple rolls. A piece of set dressing or character introduction you think would be cool but don’t benefit you any? Inefficient! There’s a few cases where it’s worth it to spend a point inefficiently over not spending at all, and there’s room for splurging unless you’re really feeling the squeeze, but, again, if you’re just thinking instrumentally – authorial power becomes [resolving things more efficiently than the game mechanics allow] power. And, of course, then a GM needs to be on watch for the players making proposals that earn them too much benefit. Being locked to a gold standard goes both ways – if a Fabula Point can resolve a whole adventure, then actually spending them on rolls is a significant waste. And then things like [no fatigue] are back in the conversation.

In other words… by putting instrumental play in the pot, suddenly authorial power in the hands of the players is a lot more muddled. (Which might be one of the reason why it’s “safer” to let the players write in the setup phase.)

From a perspective of writing a story, fully instrumental play is really inefficient. Things are already bad enough that the power is divided so unevenly – the GM having to over the whole world and piecing events together into some semblance of coherence, while the players just handle the characterization for one guy. But, even when distributed more evenly, if everyone’s playing to win, it’s still a mess. Heck, see just two paragraphs ago. “Gosh, it’s a good thing there was this convenient bridge across this chasm” may be a series of events it makes sense for a player to try to write, but, is that compelling? Is that satisfying? From a perspective that doesn’t care about if the players are winning or losing, that’s pretty bad. In practical terms, it puts the players in the role of actively sabotaging the story. They want to make it go as smoothly and conveniently as possible for our heroes. If the GM isn’t working to make that thematically coherent, it won’t be, and they’ll be facing a major uphill battle to do that.

Commenting with finality on what makes a good story would be rather arrogant, even for me. But I do think it shouldn’t be that controversial if I posit that a story where the heroes win all the time as efficiently as possible wouldn’t be considered the most compelling. And, to be clear, I don’t just bring this up for the idea of compiling an RPG’s playthrough into a story after the fact – I mean in terms of experiencing the process of play on the dimension of it being something narrative-like. Finding interest in the paths the characters take and the way the world evolves. If those paths are all efficient, effective, and calculated… I don’t think that priority is entirely satisfied.

Really, this is a muddle that exists in storytelling’s priorities, even pushing against itself. So the problem is arguably fundamental.

Have you ever read a romance story?

I have. They’re a not-terribly-guilty-but-still-slightly-out-of-character pleasure of mine. There’s also quite a lot of them out there. Love is a popular topic of art, turns out! …Ish. Romance stories, a lot of the time, aren’t actually about romance, in the way that D&D is about fighting (ie it’s what happens most of the time). Rather, they’re about the process by which one gets to a romance – they’re about romance in the way that D&D is about beating whatever enemy is set to be the big finale. You’re focusing on the process to get there, and once you do, you stop, because the exciting part is over. Usually, for a romance, the process is a lot of heartbreak, misunderstandings, emotional turmoil, occasional kidnappings, that sort of thing. A lot of failure and struggle to move in the direction of the endpoint, and the tension of that is the fun part.

I’ll call this the [romance problem], and I immediately think this is a misnomer, because, I really like that sort of thing. I don’t think it’s a problem at all. But, relaying a perspective from the people in life for whom love is not just a fictional conceit, this can get pretty frustrating. Sometimes you do want to see the experience of actually having a healthy loving relationship mirrored, and focused on, and when everything presented as “a story about love” isn’t doing that, it’s a consistent letdown.

RPGs, by their nature, are shaped by the [romance problem]. They’re only able to structurally support what their structures are built to support. D&D can’t continue once you take out the last enemy, unless bam there’s a new enemy to be dealing with. Lancer doesn’t continue if you decide to quit your government job shooting at tyrants with a mech for a more peaceful life, unless that life is significantly not peaceful. A romance has to stop once the characters make nice, unless they continue to be emotionally tense and difficult, or we shift to focusing on new characters doing that. Or, unlike RPGs, they just shift to a different tone about them – but a romance story RPG would mechanically structure around the difficulties and failures to connect in a healthy relationship, and you’d be fighting against it all the way.

Now, let’s imagine a romance where the characters resolve their misunderstandings and obstacles at the first opportunity, laser-focused on making this connection work, and the world rewards them.

That… actually sounds pretty funny. But it sounds funny, you know what I mean? That’s a gag of a story. It’s lampshading what romances are like. It doesn’t actually satisfy the people who want to see a story about a healthy relationship, because it’s still in the shape of overcoming tribulations and miscommunications – but I’m not too pleased, either, ’cause where’s the drama! Where’s the characters failing because of who they are? Taken seriously, one might be able to enjoy it for what it is, but it doesn’t really satisfy the interests of what it’s presenting as.

Giving expanded authorial domains to the players ends up with stories like that, if the game has a goal and the players are being instrumental about it. In a way, that happens even without a more equitable capacity to write in the hands of the players, but it’s so much moreso. Hence, for games built for goals, writing has to be constrained playerside, like any other tool in the box. In Exalted, it’s a 1/scene roll you can try, and only have a meaningful chance at success if you invest in a skill which has that roll as its primary use. In Wilderfeast, it’s entirely happenstance if you roll luckily enough to have spare successes to burn on details, and they aren’t all that impactful. Fabula Ultima has a whole metacurrency with a different consistent use case. None of these games could actually just let the players write things unabated. If they did, they would have to remove their focus on instrumental play entirely, and they’re all designed for that. So, instead, these limited affordances exist, and the games can only hope that a vigilant GM and maybe a sense of restraint on the players’ side will keep things in bounds. We can only have the romance problem if the main characters really are struggling – the more they can just write their way out of it, the less they will.

Fluff and mirrors

This is a situation where Legacy‘s approach fares a bit better. You have options like stat arrays, specific powers from certain lifestyles or doctrines, and in a section for each playbook they list bundles of abilities that form various playstyles when combined. The game is interested in composing a coherent build for your faction, with particular strengths. And, when you do that, the options you’ve taken inherently invite your narrative context to fit in certain ways. It’s also possible to pick options for their authorial hooks and get a build from that, but, you will be mechanically disadvantaged to some degree, that’s the natural price of not focusing on instrumental logic. Legacy by its design tries to allow for both approaches, and it works, to a decent degree.

This format is how a lot of more mechanically-dense games make narrative representation work, actually. You pick abilities to cohere based on what build you want, what you want to be able to mechanically do. Then, once you’ve selected all that, you look it over, and it gives you a set of narrative hooks and concepts that affect what you write about your character. This is a way that the system pushes into the players’ domain, not just the GM’s. These powers are all lightning blasts, so let’s be a bit sparky, shall we?

There’s an adage, in some of the RPG circles I run in. “Fluff is free.”

Let’s suppose I picked out a bunch of lightning blasts. I like the nonstandard multitarget aoes and the charge mechanic, or whatever it is. They form a coherent build, and it’s a playstyle I enjoy, and the closest other options don’t meaningfully work the way this build does. Mechanically, I’m entirely satisfied.

Aesthetically, however… who wants to be a lightning mage? Don’t answer that. Let’s assume it’s not my speed. My ideal character is throwing fans of darts out from his sleeve, and it’s very cool, and maybe I commissioned some art about it. The game doesn’t even have darts as an option. I’m just using the lightning, and making its aesthetics something else.

That’s the “fluff”, and the “free”ness is that I can do that at all. That I can say, “here’s my list of powers, the baseline aesthetic for them is lightning but I want to do cool dart tricks instead” and it’s not breaking the rules any. It’s changing the element of the powers that doesn’t matter – it’s not like it changes how it plays any, if it’s lightning or darts. This way just makes me happier, on an aesthetic level. It doesn’t cost the game anything, and it makes me happy. Why not make that free?

Generally speaking, it’s an adage I stand by. It’s also coherent with what’s been established previously in this post – the domain of a player allows them to write something that is true, so long as it is constrained to being about their character and the actions they take. Even if the borders between domains are running hot and war is on the horizon, that should be fine.

Suppose, though…

Suppose my super cool dart boy gets imprisoned. Alongside the rest of the party. We flubbed a fight, or something. It happens.

And suppose that, among the various abilities picked up over the course of the campaign, I got a simple reposition power. Slide 2 spaces 1/round, ignore intervening terrain, don’t provoke reactions, open one seal. Whatever. Mechanical jargon. It doesn’t matter. What does matter is, in altering the fluff a bit for my dart boy, I decided he has some sort of cursed amulet that lets him teleport a little, and even dip his darts in curses to explain some of the attack effects I’ve picked up. Cool, right?

Well, I just said that he can teleport. We’re stuck in a cage. Can’t I just teleport my way out?

In this (and almost no other context) I’m rather conservative. I think the simple answer is, no, you can’t. It’s fluff, and it’s called that for a reason. The way you fluff your powers doesn’t matter, so it’s free, but it also doesn’t matter – you can’t squeeze utility out of it just because of the aesthetics it has. And, to be clear, I can understand why that would land poorly with some people. But, if it is the case that fluff can give that sort of tangible utility, and you still let it be free, then, well… actually, my darts were the manifestation of a power to make physical objects out of anything I imagine. So I can also conjure lockpicks that way. My ranged attack is me traveling back in time and lightly injuring their grandparents, I can totally do time travel outside of a fight too, right?

It’s the troubles of instrumentalization again. The more impactful a given piece of writing can be when put into the world, the harder it is to just let a player do it, or they’ll turn it into an effort to win. Trying to win is one of the core jobs of a player, after all. What’s the optimal fluff for a given powerset to get the most narrative utility out of it? I have no idea, but if that question is being asked, then you’re better served not letting people refluff at all (and also hoping that the default aesthetics of the powers are roughly equally matched in terms of narrative power, which is also often not the case).

And… if you look at what I just read, it’s, “if we give the players any tangible authorial power, it becomes a mess, so let’s constrain their domain even further to avoid that.”

In other words – the instrumental arrangement is why the power is so imbalanced. If the players have a goal, and they can write what they want, they speedrun the romance and skip all the tension. So a GM has to let them write around the margins, and nowhere else. For it to be free, it has to be fluff, in other words.

In the margins

As it happens, there are other marginal sections, other bits of fluff, beyond what gets normally classified as such (the aesthetic presentation of one’s character). In fact, you can kind of broaden the category significantly – any part of the world that does not tangibly impact the process of overcoming obstacles and following the mechanics of the game, notionally, should be “free” to write in. Even if a player writes into them, a trespass into the GM’s domain, that’s probably going to be allowable. (Though there’s probably qualifiers based on the ever-absurd invocations of “common sense” or the like – declaring today to be an eclipse might be seen as a player getting uppity, and thus worth a veto, even if that would have no impact on proceedings one way or another.)

Some aspect of this, I believe, comes from the format of play. In recent years, the majority of games I’ve played in have been in text – both in a usual session format, and in asynchronous posting. I find this more comfortable for a few reasons, one of which is the propensity for long-windedness I’m sure you’ve observed by now. There are upsides and downsides vs a game done verbally, and some systems are affected more by one or the other – but most relevantly to this conversation, text has it significantly easier to “slip something by,” in terms of writing.

If, in a game, I were to say, for instance, “the wind blows by,” out of context, that might feel a bit strange. Even if I do it before a short moment of dialogue, or a long one, it would be somewhat notable. Going for several sentences of description would be downright self-indulgent, as a player, and making a habit of it would never go uncommented on, even if it were accepted as an eccentricity.

If, in a game, I were to type all that, interwoven with the other dialogue and narrations of character action, it would require a lot more to become noticeable. I’ve done that. I’ve made posts, as a player, that include whole paragraphs simply describing and establishing pieces of the world, within the margins of fluffiness where they won’t cause any mechanical concerns the GM might feel compelled to litigate. The only comments I’ve gotten on them are when it gets really self-indulgent and expansive – the ceiling is much higher than an analogous situation delivered verbally.

Another form of engagement that I have found to be easier in text, and constitutes an implicit capacity to write into the world, is conspiracy. Shooting a proposal to another player, especially the GM, is awkward to do in person, and even in a voice call online, especially if it’s something you want to discuss just with the GM. As a result, those sorts of conversations don’t tend to happen so much, or, when they do, they’re between sessions – and, usually, in text formats anyway (like emails). In the text games I’ve been in, however, having both a public chatter place to discuss the game, and personal lines of communication between each player and the GM, have been very normalized. Within that normalization, alongside the other benefits of having accessible communication channels, has emerged (by which I mean, I intentionally introduced) the practice of [scene framing].

That is – pitching, to the GM or other players involved, “hey, I would be interested in X scene happening next.”

This is pretty useful for setting up specific character interactions, for deciding on where to set scenes and what people are interested in seeing, and, once the ideas start flowing, getting a whole itinerary of near-future moments to explore. It’s a technique I picked up from my time in online freeform roleplay, where communication and advance plotting of scenes and their direction was the only mechanism being used (beyond all the implicit social ones, of course). It’s very handy in a lot of ways, and it’s something I try to make use of in games when possible, but, of more pertinent interest to this post – framing a scene in advance is a form of writing. It’s, again, subject to GM veto, but, where normalized, a player going “hey, I want to have an interaction with X character, maybe in Y location” is a relatively strong capacity to establish: not only is X character accessible, they are accessible in Y location, and in the near future. And, that isn’t just fluff, that can cover some pretty significant steps forward, depending on what the goal of the characters is right now. Normalizing this is, in a meaningful way, an expansion of player capacity to write.

Now, what I don’t want to do is pitch this as a solution to what we’ve discussed above; in part due to my prejudices. I am a system-minded person, I care about what the mechanics of the game do and want to be molded around that core. There are, really, a lot of these sorts of non-game-grounded methods to redistribute the balance of authorial power. The GM just not vetoing any narration, and accepting whenever the players say “hey, wouldn’t it be cool if X?” covers that entirely, for instance. But, these are non-deterministic. The power being redistributed is done by the grace and habits of an individual GM, entirely disconnected from the system on its own merits. Something like scene framing could be formalized by a system, I’ve had thoughts in that direction in my various design works lately, but using it for a system that doesn’t do that, and presenting that as a more even distribution of power, is, at best, disingenuous. A game is, out of the box, only what the system mandates. Anything else that the players layer on top is nice, but not universal, and not necessarily [true of the game]. That’s the baseline principle of design that I hold to in my analyses, and I don’t want to be deviating from it here, even if I can recommend this as a method in broad terms. So, the question is what systems on their own merits do, in terms of distributing the capacity to write.

This is why things like Quests in Glitch interest me so much. (If you read the instrumentalization post when I linked it, you’ve seen these already.) Not only can the players just write their own, alongside picking from a list, each one comes packaged with explicit and implicit writing capacities both – actions that you can just declare true, and larger goals that the GM is obligated to put in your path, aligned with the thematic bent of whatever the Quest is about. (Which is sometimes bad! There’s multiple Quests about spiraling into depression in one way or another.) They’re properly-structured and mechanized methods to grant authorial power to the players, even while the game is instrumentalizable in other dimensions (it’s got a whole resource management game at the heart of it), and it weaves in similar scripting-the-future capacities to scene framing. In terms of putting authorial power in the hands of the players, it’s quite a nice format to iterate on.

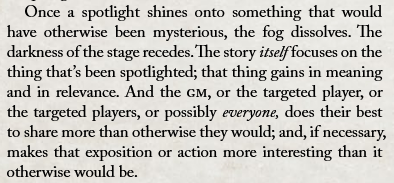

That’s not the only thing like it in Glitch. Honestly, the game is a solid starter point for systemized player authorial power within a GMed context while still having instrumental play relevant to the players. Each player comes with a budget of Spotlights per chapter, which, alongside literally regulating the spotlight between players (since everyone has to go through their budget, so if a player is lagging behind the focus moves to them to catch up), serves as a limited authorial capacity.

There are a few other uses for Spotlights, including ones that let you inflict even more authorial power when in the alternate void-dimension that you have more control over than reality (the game’s premise is complicated enough that I could make my own gushpost about the lore, so let’s just move on for the moment), but you can see the elements here. You spend your budget of Spotlights to take parts of the world and make them have more information to give you. Center them in your perception, and the importance of the story. You can take an NPC and push them into new characterization, even if the GM was going to have them be a gloomy mess for a while. (That one happened to me, as a matter of fact.) These are alongside the in-some-ways-authorial powers that the game gives its players as a matter of their diegetic capabilities. You have a lot of options to write things into the world, in Glitch. Budgeting Spotlights is part of the gameplay as much as budgeting your more active powers is, but, the game tends to give you more breathing room with them, and the GM’s interpretive power does work something like a veto – but these are, still, powers the player just has. By including these systems, Glitch expands the domain of a player in ways that even setups like Fabula Ultima‘s don’t.

A farewell to arms

Honestly, for as much as I’ve milked it, I kind of don’t like the domain analogy.

From an instrumental perspective, as we’ve covered, there’s an important utility to it. If you don’t understand the bounds of what is fair to do and what is unfair, you can’t play your best and be satisfied with a win. When those bounds are socially defined, and applying pressure to the GM will let you expand them, it muddles it even further – did I win because I did my best, or did I win because I wore down the will of my friend? Can I say I’ve done my best if I didn’t wear down the will of my friend? The GM veto and capacity for arbitration has shown up many a time in this post, even in mechanics that I’m mostly praising. In a sense, my thoughts on stunting all apply here, as well. I don’t really think there’s a way to get around that, too, if you’re keeping things within the instrumental milieu. If you have goals, and obstacles, and player tactics centered around how well they can manage those obstacles, or even only a couple of those elements – the border is going to run hot. You’ll need to navigate the diplomacy at the table, to avoid it turning into a war.

And, for as much as I enjoy instrumental play, I think that’s a shame. As a GM, I like doing invasions into the players’ space sometimes, in this analogy. I’ll tell them part of what their characters are feeling, how they would instinctually react based on what’s been established about them, and where they might want to go from there. That’s another instance of “here’s a trick that has nothing to do with the mechanics,” so, take it with a grain of salt, but it’s only something that can be done if the boundaries of narration aren’t quite so clear-cut. That requires the players to figure I’m not trying to beat them down with this – which means them not expecting me to be putting obstacles for them to have to overcome. There’s a sort of trust there that can only exist if the arrangement isn’t too instrumental, isn’t that adversarial. And I think that’s why I find implementations like Fabula‘s to not really resolve the problem for me – they’re certainly better than nothing, but they’re coexisting with an understanding of what the GM is here for and what I’m here for. If I lose that understanding, the game’s mechanics are much less useful, the whole thing is centered around a fleshed-out combat system, after all – but if I keep that understanding, whenever I write, it’s a play for power, and whenever the GM writes, it’s a setup of something I probably need to keep an eye on.

The value of fluff, of writing in the margins, is that you can do it without it being a threat. The GM can figure it won’t support a scheme, and veto it if you try to let it – and the players can let it slide without having to keep an eye on every angle, if the GM is content leaving things as aesthetics. The value of systemization, of things like Quests or a hypothetical formalized scene framing, is that it can coexist and intertwine with instrumental play, because the mechanics themselves can be built to not let the players slip by and get too powerful.

If you ditch instrumentalization entirely, then systemizing it is still helpful, because systems give structure to players – but you also need an idea of what the players are actually trying to do. And “tell an engaging story” is, in that dimension, a circular and pretty meaningless goal, which is why you’ll see things like Belonging Outside Belonging games come with more specific moods you’re trying to elicit when playing a given character or environment element. (And even those have some amount of token-optimization gameplay to them, as a rudimentary chassis to push thing forward. I think it would be somewhat difficult to find more than one or two games that are entirely free of instrumentalization.)

Ultimately, I think my conclusion is one that I’ve been orbiting in the past several posts. Trust is an illusion. Even freeform roleplay is founded on a baseline of what are the boundaries you can’t cross and the things you shouldn’t do, where the domain of the other player begins and you don’t have a right to touch unless they’re comfortable with it. And I don’t think that’s a problem, per se, I think “trust is an illusion” is an applicable lesson to the social entanglements we have even beyond RPGs, but I do think, as designers, it’s an important thing to recognize. Where we take trust, and collaboration, and authorial generosity for granted, the systems we write can’t. But they can make things explicit. They can say, “this is a power to write, you may do so”. In a way, that’s the most fundamental thing they do. The list of skills in Shadowrun defines a set of actions you can take. Some games will be more or less persnickety about how much that covers the entirety of the actions you can take, but they ensure a minimum. A player can always narrate something in line with at least this much, and the system will support it.

People rely on trust to cover the space between [what my character does] and [what exists within the broader world]. The GM has implicit dominion over the borderlands, and the players can move as far as the GM’s grace will let them, maybe.

As designers, we can do better than trust. But that starts with understanding the shape of what we’re building on. One large domain, and several tiny ones, trying to branch out.

Usually, that’s not what writer’s rooms look like. But it doesn’t have to be. This isn’t a demand that every player get equal authorial billing the whole time, especially not if you do want there to be instrumental gameplay to it. But room to expand beyond what they’ve got is a blessing for players of all stripes, and rules can support that exploration. So, they should! Everyone’s writing. The system should give them room to write. That is, in a sense, what RPGs are for.